In one’s way of seeing lies one’s way of action.

—Alfred Stieglitz, photographer

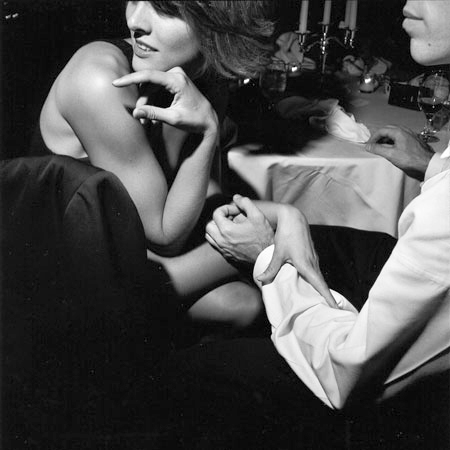

Angel of Choice © Franco Salmoiraghi

The photographer closely observes a Japanese Butoh dancer

commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing.

Both science and art often derive from human observation over long periods of time. Comparing, contrasting, and analyzing the fruits of immediate perception leads to stunning insight and pushing the boundaries of what we know. No matter where we locate ourselves on the political spectrum, an active conscience dictates that we keep our minds and eyes wide open to ongoing discovery through the senses, tempered by the critical mind.

Seeing needs cultivation. Observing our surroundings, observing others, observing the dynamics of human society, and witnessing the forces of the natural world are the key to knowing about the universe. The vast storehouse of human knowledge in science, medicine, art and literature, psychology, religion and philosophy, astronomy, technology, language, and every subject imaginable; these all stem from sustained human inquiry. And, we have likely only scratched the surface, uncovered an infinitesimally small portion of what we can know about the world and the essence of things. It is now up to us. The future rests in our hands. Those who have gone before have added their wisdom and insights. Now, it is our turn. All we need to do is observe — with attention. Complex worlds await their encounter with our inquiring awareness.

Observation forms the crux of what is normally known as vision. Sight is the dominant human sense, yet most people take their vision for granted and do not realize its vast potential. Contemporary education does little to teach students how to see. By seeing, I am referring to the human capacity—beyond but including physical sight—to know and interpret the world through direct perception. Most people don’t know the uniqueness of their own vision, much less how to cultivate it. How does one learn to see? In what way is our capacity for keen observation challenged, cultivated, and nourished? A camera can help you regain the wonder of sight.

The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.

—Dorothea Lange, photographer

Seeing can be learned. You can sharpen your observational skills and use them for creative work and in your interactions with others. Photographers, writers, filmmakers, and artists are trained to see beyond surface appearances and speak about the particulars of the human condition. Parents and teachers seem to instinctively perceive the needs of children. Caring and responsible friends and partners treat direct, face-to-face perception as the primary means of knowing another. Learning to accurately read people helps immeasurably in one’s personal and professional life. I know photographers and writers who spend days, months, or years in close scrutiny of their subject before translating the material into novels or visual projects. A friend, who teaches dance in Seattle, studies the flow of human movement, posture, and gesture on the streets and in public spaces for months at a time as inspiration for her contemporary choreography. The act of simple seeing can bring the world to life. Writer Bonnie Friedman claims, “We can do this: we can observe. Things are saturated with significance.”

Observation prods our creativity in unsuspecting ways. You do not know what you may find until you look now, look again, and look constantly. Photography can help hone your capacity for observation. The visual language of photography invites a perceptual interaction with the world in a way that corresponds to the principal, graphic elements of the medium.

The Five Visual Elements of Photography

In writing, as in photography, an often-stated admonition is offered to help bring your scenes and images to life: Show, don’t tell. Reveal the carnal details of the scene. Use those details to show and, by inference, tell the story. Images do not only speak to the mind, but also activate the heart and senses, and spark the “blink” of intuition in which the viewer recognizes in an instant what is being communicated. Telling can be dry and analytical in a way that cannot touch the emotions. If you are only going to tell, why not use words instead of images? By including the messy materiality of the subject—the sheer physicality of color, light, posture, gesture, clothing, and even its flaws—you can ignite the viewer’s interest and invite them into the world of intense sensuality. When I use words like carnal and sensuous, I’m referring to the exuberant chaos of life, complete with the details and the things of the everyday that are physical reminders that we are sensate beings and that the myriad stuff of the senses are resplendent carriers of meaning and significance.

In teaching photography, I’ve given a good deal of thought to both the physicality of the medium and its conceptual potential. Over the years, I’ve distilled the demands of seeing with a camera into five visual elements that you need to pay attention to when observing and photographing a scene. These photographic elements can help stimulate your observations and, when used effectively, can dramatically improve your photographs. Each of these components are ways of shaping your sense impressions and focusing your ideas into form.

The Frame

The Light

The Moment

Use of Color and Tonality

Treatment of the Subject

When these elements integrate together into a coherent expression, your photographs can spring to life. The skill of the artisan is to bring the visual elements together in a way that coheres and reconciles differing elements, that is a fully integrated expression for the viewer. Let’s examine these five elements.

The Frame

Beginning photographers often place the subject in the dead center of the frame, like a loaf of bread sits squarely centered in a breadbasket. The disease of centeritis, while not fatal, takes some time behind a camera to fully heal. You need to take responsibility for everything in the frame. Your observations of the world can discern what is relevant, important for showing your story, and what is superfluous and can be taken out. The discovery of context—what lies in and out of the frame—is a hugely important communication device. You must remember that truth and facts are two different things. You want to reveal the facts that tell the truth, as you see it. You are not showing the truth of something as you photograph it, you are pointing to its significance using metaphor and allusion. Ayana Mathis writes in the New York Times,” Metaphor is a potent carrier of truth, particularly those nearly inarticulate truths we can only approach through juxtaposition and allusion.”

What we juxtapose together and how we use the frame is itself a metaphor. In contemporary photography, the edges of the frame themselves are used as a central part of the composition. Interrupting a movement or framing tight allows the action to complete itself outside the frame. It alludes to what surrounds the subject. While framing loose and placing all of the subject in the frame makes the image a complete entity, separate from its background. When you place objects very close to the edge of the frame, a dynamic tension ensues, a vibrating region of energized relationship between the subject and the palpable frame. When moving objects close to the edges of the frame, visual heat results.

There are many rules of composition all of which have some value. These rules have their uses, but they can easily become formulaic. I prefer Minor White’s argument that composition is merely the “strongest way of seeing.”

The Light

Light is the currency of photography and what reveals the things of the world to our eyes and brain. Many different types of light exist in the world. Each place on earth has a distinctive quality of light. Each season has its own light, and time of day becomes an expressive element in the photographer’s hand.

Watch the light and savor it, always. As an observer, pay careful attention to the light of the world and what it does to objects or people. How does the light make you feel? Does the light heal? Does it shout? Does it envelop the subject or overwhelm it? Does it show the volume and depth of an object, or flatten it? Study good photographs and observe the photographer’s use of light. Your attention to light is key to successful image-making. And your use of light is indicative of how the viewer may feel about what they see in your image. Often I have come upon a subject with great interest and with an anticipation about the subject’s potential. But the light was wrong and not in accord with how I wanted to communicate my intent and vision. So, I would dutifully return to the subject time and again in different weather conditions and light. With enough persistence, invariably they day would come when my senses were shocked into the recognition that this is the right light. I couldn’t see it or imagine it before hand, but I just knew and intuitively recognized its rightness in the moment. Ansel Adams wrote about this momentary discovery of the right conditions: “Sometimes I feel that I have come upon the subject just when God is ready to have the shutter clicked.”

Experienced photographers can control light in the studio, and to some degree, in the field with supplementary lighting. Street and landscape photographers accept the light that is found. Traveling photographers are at a disadvantage as they often show up in less than ideal lighting conditions and do not have the luxury of returning to a place again. Portrait photographers often prefer the dimensions of natural light over controlled lighting. Your exposure and post-processing controls can influence the light to some degree. But mostly you make do and learn to use the light that you find or can influence to small degrees through reflectors or hand-held flash and lighting units.

Often, you photograph what is in the light that exists. The Zen attitude of impartiality and lack of judgment comes into play. The problem with most observers is that they react emotionally to light in a highly subjective fashion. Try to get beyond this. View the light, study its potential at all times, even when not photographing. Examine how the light plays across your feeling and senses like sounding different notes on the piano touches you in different ways. Light is the essence of photography and one of the principal expressive elements in your images. Get to know its full range of possibilities intimately.

The Moment

Photography immortalizes fleeing moments in time. It’s such a simple idea—yet so complex in its realization and rife with political, social, and personal implications. Which moment and why? Taking a moment out of the flow of time and making it memorable demands sensitivity, awareness, and active reasoning. The moment you choose becomes an interpretational vehicle for your worldview and your overt or hidden attitudes. Much of your thinking is done before you snap the shutter. There is no time to think in a moment that requires instinct and spontaneity to capture. Self jugtyt6vrfeawareness and your attention to the world are allied in your search for your perfect moment. The perfect moment cannot help but reveal many aspects of yourself: your psychology, your social and political views, your conditioning, and natural tendencies. It is your moment to select out of the flow of life, and it reveals as much about you as it does the world itself.

Watching the subject with close attention can teach you many things. Sometimes you notice a certain posture or gesture or facial expression that feels natural to the individual. Sometimes you can see their mask drop away and something of their character is revealed. Above all, you may notice a symphonic rhythm to the activities in front of you, rising and falling in intensity building up to a crescendo, or humming along with a certain tone, punctuated by the drumbeats of emphasis as certain events take place. As an observer and photographer, you may often be surprised or astonished by simple everyday moments that defy your expectations or counter your closely held opinions. If that happens, good. That’s what observation is for—to open your mind.

Use of Color and Tonality

Color and value, or tonality in black and white photographs, convey feeling and emotional resonance. Like the rhythms, harmonies, and dissonances of music, the color and tonal relationships present in a photograph play over a wide range of human emotion and states of being. They are the adjective to the noun, the modifier to the verb. They create beauty, enhance meaning, and influence the viewer on conscious and unconscious levels. Color and tonal relationships are felt and sensed way more than they are analyzed or intellectualized. The lush language of color and tonality are used in art and design as primary communication tools and can take a lifetime to master. If you want to communicate visually, color and tonal relationships are a measure of the photographer’s sensitivity, skill, and aptitude for subtlety—and can never be an afterthought. As with all the expressive elements of photography, the acuity to perceive and effectively employ color can be learned.

In today’s technological environment, you are not limited to the color you see. Image editing software like Photoshop—and even the darkroom—provide an expansive set of tools to control, correct, and enhance tonality and color. In my experience, taking the photograph constitutes only a portion of your creative intent. Post-processing offers a world of expressive possibilities. Even if you choose to limit your creativity to camera controls, at least become aware of the capabilities of post-processing software. The time may come when you will need it.

Treatment of the Subject

Many of my students begin their photographic journey with some variation of the question, how do I make a good picture? I answer them that a good picture cannot be defined merely in the abstract. Photographs are about something. They tell stories, convey meaning, and are often a mixture of fact and fiction. A good photograph may result from a dialogue with the world or a conversation about ideas. Or maybe, they spring from the photographer’s fanciful imagination or from deep self-inquiry about identity. Images may convey hope and beauty or arise sharply from outrage over injustice and troubling conditions. Some photographs honor the everyday moments of our lives, while others shock our awareness by showing us conflict and strife in parts of the world far removed from our comfortable reality. Some grow from struggle, some show the world we aspire to, and some mirror the artist’s search for consciousness and realization of their human potential. One camp of acutely concerned photographers strive to show, in James Agee’s words, “the cruel radiance of what is.”

Sugar Cane burn, Maui, HI © David Ulrich

Harvesting of sugar cane takes place by burning acres of stalks to the ground in pre-dawn light—resulting

in apocolyptic blazes lighting the land. This was my first image of the new Millenium and symbolizes, for me,

the consequences of the human footprint on the earth.

Indeed, the content of effective pictures often transcends the mere picture plane. In the 19th and early 20th century, serious photographers battled against the Pictorialist movement, which treated photographs like parlor paintings and spawned romanticized images with no other point than making a pleasing object. We see similar kinds of rampant pictorialism today since powerful tools like advanced cameras and Photoshop are within everyone’s reach. Unfortunately, many budding photographers have not had even rudimentary visual training and lack awareness of effective visual communication. There is much triteness and narcissism in many images that I suspect the world could do without. Becoming visually literate—able to communicate effectively through images—is one of the many benefits an earnest involvement in photography can provide.

You begin from where you are. What is most urgent; what do you deem important to explore and express? The Russian painter, Wassily Kandinsky, defined one of the most important motivations that you can find for creative work as “inner necessity.”

Sketching ideas, by responding freely and naturally to life through a camera, is a potent form of discovery and can help clarify your concerns. In fact, many photographers take pictures and writers put their pen to paper in order to clarify and expand their ideas, without knowing exactly what will come through their camera or pen beforehand.

What way of seeing grows naturally out of your enthusiasms and interests? What kind of knowledge and values do you embody stemming from your life experience?

The last word in this essay belongs to one of the great explorers of human perception and consciousness, writer Aldous Huxley from The Doors of Perception: “In a world where education is predominantly verbal, highly educated people find it all but impossible to pay serious attention to anything but words and notions. … Systemic reasoning is something we could not, as a species or as individuals, possibly do without. But neither, if we are to remain sane, can we possibly do without direct perception … of the inner and outer worlds into which we have been born.” Simply stated, seeing is a form of knowing.

Adapted and excerpted from Zen Camera: Creative Awakening with a Daily Practice in Photography by David Ulrich. Forthcoming from Ten Speed Press/Random House, February 2018.