Excerpts from an interview with Matthieu Ricard

The full text of this interview appeared in Parabola magazine Vol. 37, no. 2, Summer 2012, titled Alone and Together.DU: Matthieu, we are trying to understand how a larger intelligence is available to us, and how we can come together to contact this intelligence. Philosopher Jacob Needleman asks: “How to come together and think and hear each other in order to touch, or be touched by, the intelligence we need?”

MR: First of all, there are many understandings of even the word intelligence. Usually there are two parts in Western education. One is the acquisition of as much information as possible: of geography, science, and so on. And the second is the development of intelligence, which is posited as the faculty of reasoning, of understanding. You are trying to develop a tool of reasoning, of making associations, of analyzing situations— which is really only a tool. And a tool, like a hammer, can be used for building or can be used for destroying. As the Dalai Lama often says, a typical example of that is 9/11—which was an extremely smart use of intelligence with the means to create enormous human devastation. An intelligence that did not hesitate to use human beings as bullets to destroy other human beings. So that’s a typical example of a sharp intelligence which, without the proper motivation, can be an enormous tool of destruction. So intelligence itself is just like strength, skill, or energy or money or whatever and can be used to destroy or to build. Intelligence can be accompanied—especially in education—with the development of human values, an acquisition of the crucial importance of the motivation that underlies every of our actions. We cannot predict the outcome of many of our actions, because there is a limitation in what we know—how things are going to unfold, or happen, and the consequences. Yet even the most dumb person can check his or her motivations. Am I doing this just for myself, out of selfishness or to actually harm others, or I am doing it for the double welfare for myself and others?

So we come to the idea of the total need of first developing human values and the right motivation, which is loving-kindness. We are part of others, so we cultivate love for everybody including oneself. So that’s a very important component of life, of education. And so intelligence alone—it’s great to have it. But without the values, it can’t be anything.

Now there is another aspect of intelligence that is a deeper understanding, which is linked with wisdom and relating to the deeper nature of mind, and also of understanding the nature of phenomena, because those are interdependent. That kind of intelligence is more like a type of wisdom, which has a clear insight into the nature of reality and of your own mind and consequently of the minds of others.

If you clearly identify in your own mind the wish to be safe, the wish to be happy, the wish to be flourishing, then you can also appreciate that and understand that in others’ minds. I would say that kind of insight is more than intelligence. Insight is deeply linked with values, with the distinction between destructive and constructive emotions and states of mind. And also a correct perception of reality is very important. If we superimpose our mental constructs onto reality and say, for instance, things are permanent and I want myself, my dear ones, my possessions to last … Whereas in the constant dynamic flow of transformation, all of our perceptions of reality are going to suffer from that attitude. All of a sudden we are confronted with sudden change and then your superimposition will collapse and cause suffering. So insight is broader into the nature of things, and also the quality of things in terms of consequences in terms of happiness and suffering. So that is true intelligence, or true insight, or true wisdom.

DU: It’s entering a larger flow. We enter a larger connection with other people and with the world at large.

MR: Well, larger in the sense that you begin to realize what it is. You realize that for instance loving kindness, happiness, cannot be a self-enclosed phenomenon. Selfish happiness is a contradiction. Real happiness can only occur through and with others. Precisely because your understanding of interdependence and cultivation of loving kindness is a fundamental component of happiness. That is why selfish happiness does not work. That is also why a fundamental understanding of reality is important. Because interdependence and loving kindness are closely connected. So a larger perspective means understanding that the real fabric of reality is interdependence—for phenomena, for living beings, for the environment. And hence the Dalai Lama often emphasizes the concept of non-violence: to human beings, to animals, and the environment, because they are totally linked. You cannot disassociate them. If you disassociate them, you run into trouble.

But this has to start with changing your own mind. I think the real nutshell is transforming yourself to better transform the world. it’s a sort of formula. You cannot really do humanitarian works, change your psyche, do something constructive without first eliminating some kind of mental toxins from your mind that makes you individually work in selfish ways. So in that sense independence and the change of your mind to loving-kindness, openness and so forth is how universal responsibility can be applied.

DU: Do you think that a community of seekers helps us in our search for intelligence? I find that when I am meditating with others, again I feel that something more is available then when I am meditating alone.

MR: We have a saying: community simply reinforces your sense of commitment, of engagement, of discipline. When I’m meditating otherwise I just may want to do something else. Like lie down. So if you are in a group, there is a kind of common discipline. We have an image for that that is very nice. In India they use the Kusha grass for making brooms. You have a thousand fibers of Kusha grass. Individually, they cannot make a broom. If you gather them together you have an efficient broom. So this notion of sangha, of community, is actually companions traveling together on the path. And they help each other when someone is weak, or not always going in the right direction. You see the strength of their commitment, their practice, or you see their weakness. It’s better to be ten companions traveling in the forest than just alone. The whole thing works better together. So I think the notion of community, as friends, of companions, is certainly most helpful.

This notion of emergence is important also. A crowd does not behave the same way as one hundred separate individuals. There is something more coming up than the simple sum of each individual capacity. That is what we call an emergent phenomenon When what emerges from a hundred persons or elements is more than just one plus one plus one, etc. equals 100. You have one plus one plus one equals 120. Because there is something more that emerges. That’s a very important concept also.

DU: Could you talk more about this idea of emergent phenomena?

MR: The emergent phenomena usually is dependent upon its basis or cause. Without its basis it is not an emergent phenomena. It has a quality of a life of its own. It’s simply that there is a quality that is more than the arithmetical sum of each element. In biology it is very clear, a single neuron doesn’t do anything. Suddenly when you have 20 billion neurons, and there is the basis of what we call at least the normal action of intelligence—which is not intrinsically present in the neurons—what emerges is the brain faculty of consciousness.

In other words, elements on a lower level combine to produce something that is more than the intrinsic quality of the element—new qualities appear, and that is an emergent phenomenon. And also an element on a higher level can influence the elements on the lower level. We call this downward causality, which implies that consciousness can influence the mind, or the body, and brain function or intelligence affects the individual neurons. So we might say that emergent phenomena tends upward to form a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, but is informed by its basis, which is the consciousness and intelligence that guides it. Causality is not one way. If we say that in upward causality, elements on a lower level combine to form something on a higher level, then downward causality implies that something on a higher level influences the lower level. You can call this a reciprocal causality. Thus causality is mutual, both upward and downward, and intelligence shapes reality as reality shapes intelligence. Human beings both are formed by, and form their environment. On the ascendant or emergent side, the environment and body influences the mind, and on the descendent side, consciousness influences both the mind and the body.

DU: (Matthieu notices my book on the table, The Widening Stream; the Seven Stages of Creativity, and comments on it.) And one final question, you are an artist, a photographer. What role does creativity play in the formation of intelligence?

MR: Very often creativity is confused with a spontaneous expression of one’s habitual tendencies and conditioning. You are this way or you are that way. And these emerging tendencies come out through your creativity. The artist says, “look at me.” It is selfish and narrow-minded and can be confused with knowing the nature of your own mind. It does not free us from our conditioning or from ignorance, nor does it help develop loving-kindness and compassion. Really looking at these emerging tendencies, looking at the tendencies of your own mind is very exciting, more interesting than going to the movies. Learning to shed the skin of one’s habitual tendencies, conditioning, and negative emotions—and discover the real nature of your mind—is true creativity. Now, there is another side to what we call intuition or inspiration. And there is nothing mysterious about it. Sometimes with nature or with art, you experience greater insight, a real moment of enlightenment, or a luminosity that connects you with the world or nature or others. By understanding the nature of your own mind, you naturally come to what we call intuition and insight. These moments come from your practice, from developing loving kindness and compassion, and they are moments of what I would all genuine wisdom.

Consciousness is an experience. It goes deeper and deeper into the experience, behind mental constructs and behind the veil of your emerging tendencies. You come to your natural wisdom. So intuition or inspiration is really the experience of your own wisdom. It is like seeing a small patch of blue sky amidst the clouds—and you try to widen that patch through personal transformation.

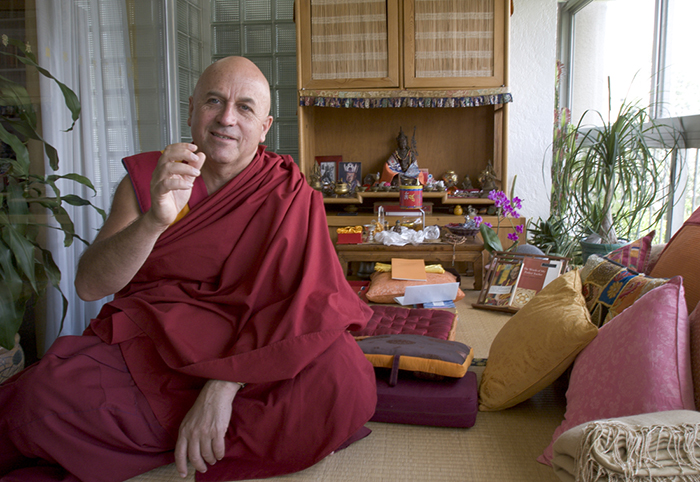

Matthieu Ricard is a Buddhist monk at Shechen Monastery in Kathmandu and French interpreter since 1989 for His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Born in France in 1946, he received a Ph.D. in Cellular Genetics at the Institut Pasteur under Nobel Laureate Francois Jacob. He first traveled to the Himalayas in 1967 and has lived there since 1972. For fifteen years he studied with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the most eminent Tibetan teachers of our times.

He is an active member of the Mind and Life Institute, and engaged in research on the effect of mind training and meditation on the brain at various universities in the USA and Europe. He has been called the ‘happiest man alive” by several neuro-scientists who have studied his brain.

With his father, the French thinker Jean-François Revel, he is the co-author of The Monk and the Philosopher (Schocken, New York, 1999), and of The Quantum and the Lotus with the astrophysicist Trinh Xuan Thuan (Crown, New York, 2001). Matthieu is the author of Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life’s Most Important Skill (Little Brown and Co 2007) and Why Meditate? (Hay House 2010). As a photographer, he has published several albums, including The Spirit of Tibet (Aperture, New York), Buddhist Himalayas (Abrams, New York) and Bhutan: Land of Serenity (Thames and Hudson, 2009).

For further information about Matthieu Ricard, please visit: matthieuricard.org and karuna-shechen.org