A Conversation with David Ulrich

—Laura Dunn

What message(s) would you leave for future generations?

I think about this a good deal. I want to pass on what has been given to me. If I have anything of value to say, it would relate to exploring creativity and vision as a means for expanding awareness and approaching the great aim of consciousness. Learning to see is a forgotten art, full of hope and promise, that assists in gaining necessary self-knowledge of who we are and a deeper, richer, truer engagement with the world. My teachers, Minor White and Nicholas Hlobeczy, were photographers committed to heightening awareness through art and photography. For them, art touched the sacred; the process of making images was a measure of one’s inner and outer states and a genuine help in the growth of being—a path towards consciousness. In this age of digital overload, I feel a strong responsibility to convey the messages of my teachers of the power of seeing before I die. I approach this as a question, to try to understand what people need. I write books, teach classes and workshops and lead groups devoted to creativity and awareness. I am deeply concerned about the growing lack of presence and the absence of striving towards a deeper attention in everyday life, which is one of the things that art and craft can encourage and engender.

I think about this a good deal. I want to pass on what has been given to me. If I have anything of value to say, it would relate to exploring creativity and vision as a means for expanding awareness and approaching the great aim of consciousness. Learning to see is a forgotten art, full of hope and promise, that assists in gaining necessary self-knowledge of who we are and a deeper, richer, truer engagement with the world. My teachers, Minor White and Nicholas Hlobeczy, were photographers committed to heightening awareness through art and photography. For them, art touched the sacred; the process of making images was a measure of one’s inner and outer states and a genuine help in the growth of being—a path towards consciousness. In this age of digital overload, I feel a strong responsibility to convey the messages of my teachers of the power of seeing before I die. I approach this as a question, to try to understand what people need. I write books, teach classes and workshops and lead groups devoted to creativity and awareness. I am deeply concerned about the growing lack of presence and the absence of striving towards a deeper attention in everyday life, which is one of the things that art and craft can encourage and engender.

How has your spiritual practice informed your photography and vice versa?

In the beginning, I had it all wrong. I desperately wanted to make images that were strong, that emulated the masters and touched something in people. If I am honest with myself, when I first began a spiritual practice through the Gurdjieff work, one of the reasons I engaged inner work was to become a better person, a better photographer. Somewhere along the way, that began to have a distinctly bad odor. Something in me knew it was not the right relationship. I was seeing things upside down. We do not engage inner work to serve our ordinary needs for accomplishment and acknowledgement. Rather, we strive to serve the higher, to seek an opening to another level. Our work can actually become a means through which we may connect with something greater than ourselves. I was greatly helped in this regard with a question that my teacher Mrs. Dooling would bring: What serves what? The higher should never be asked to serve the lower. Yet, we see this all the time these days. People meditate merely to be free of stress, do yoga for tighter bodies, and produce art that primarily serves the ego. It takes a while on the path before it begins to dawn that inner work is not self-improvement. It is something else, a striving towards another order of existence that we can touch from time to time in our best, most awake moments.

Can you talk more about how you have learned to strive for excellence without succumbing to the desire for admiration and acknowledgement? Is it wrong to seek acknowledgement for one’s talents and hard work?

I think it is a question of levels. “Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” Striving towards excellence and

seeking acknowledgement is a natural part of being human. It feels right and true to endeavor to fulfill one’s talents. And it helps form the healthy ego. However, that is only the earthly level.

Creative work engages the whole person. It becomes a search for wholeness and fullness of being. What we express in our creative work is always, to some lesser or greater degree, autobiographical. So at first we see ourselves. Over time, we begin to wish for something more, to serve something that can pass into the world through art and music, impressions of a finer energy that touch something in people that you could only call the sacred. We need this now, and the earth needs something more from us than the discordant energy that we seem to emanate as a culture.

In my best moments, with photography or writing, I have had the distinct impression of something from a deeper source passing through me, fully formed. I was and am merely the vehicle for the statement. This is what I aim for and strive towards.

As teachers of the arts and yoga we hope that we can strive towards building a bridge between the seen and the unseen, or the inner and the outer. How do you attempt to teach students to be invested in the process of creativity more so than the outcome?

As a teacher, I find myself often facing the question of which world to explore in the classroom, the inner or outer. Teaching art, by definition, reaches rather deep into individuals and opens them to a certain kind of self-knowing— a discovery of their authentic voice or vision— and a deeper engagement with outer life. A good number of people mostly want to learn the techniques and the marvelous history of the photographic medium. Yet all remain touched in some way. Photography and art are a form of engagement with oneself and the world. So . . . I often find myself needing to walk a fine line between functioning as something of a facilitator, bringing them into greater touch with their inner life, and, at the same time, to encourage a careful and rich observation of the world itself. When I forget one side, the inner or the outer, which happens frequently, I feel somehow that something is missing, that I am not offering people what they really need. In those moments, I feel the stirrings of regret and remorse, that somehow I stepped off the bridge of my own integrity.

Even with students, over time, they begin to have an inner measure, where they know in some part of themselves whether their work rings true, that it is in accord with something essential or authentic . . . or not. There can an opening to the wisdom of the heart, where we feel in some unknown way when our actions and our works are right and true. When this measure begins to make itself known, we have the beginnings of art that has the capacity to touch the maker and the viewer. From time to time, we have this kind of magic in the classroom and it is as if an energy descends into the room, that opens our feelings in a new way. As you are prone to say Laura, in those moments, god is smiling on us.

I believe in the primacy of the human spirit, and the medium through which we may connect to god, the cosmos, and other human beings, is consciousness. Creativity then becomes a path towards becoming conscious. When working in a medium, we are asked to strive towards integration. A creative act contains, more or less, an equal contribution from the mind, body, and feelings. All together. Without any one of these, it is incomplete. And when our parts are working with a kind of synergy, we can open to a larger intelligence. I don’t know what it is. The Greeks called it the muses, others have different names like inspiration or illumination.

How have you experienced this in your life?

Moments of awakening to what is have nourished me over the years. In a moment, we see that creation is whole, that an underlying unity pervades existence . . . and our existence. We recognize the primacy of spirit, and see its manifestations in all things. There is a sense of joy, of wonder . . . and an underlying remorse for what we have become as modern human beings. At this point in time, I have an abiding question of how to use the creative process to open to a greater sense of connection, to others, to life and even to god, but not to be attached or dominated by the love of art and images, which can be a trap. A beautiful trap, but trap nonetheless. I love the phrase of Carl Jung’s from his autobiography, which elegantly expresses something of my own experience: “A creative person has little power over his own life. He is not free. He is captive and driven by his daimon.… This lack of freedom has been a great sorrow to me.… the daimon of creativity has ruthlessly had its way with me… I am astonished, disappointed, pleased with myself. I am distressed, depressed, rapturous. I am all these things at once and I cannot add up the sum.”

How has the creative and spiritual landscape changed in your lifetime?

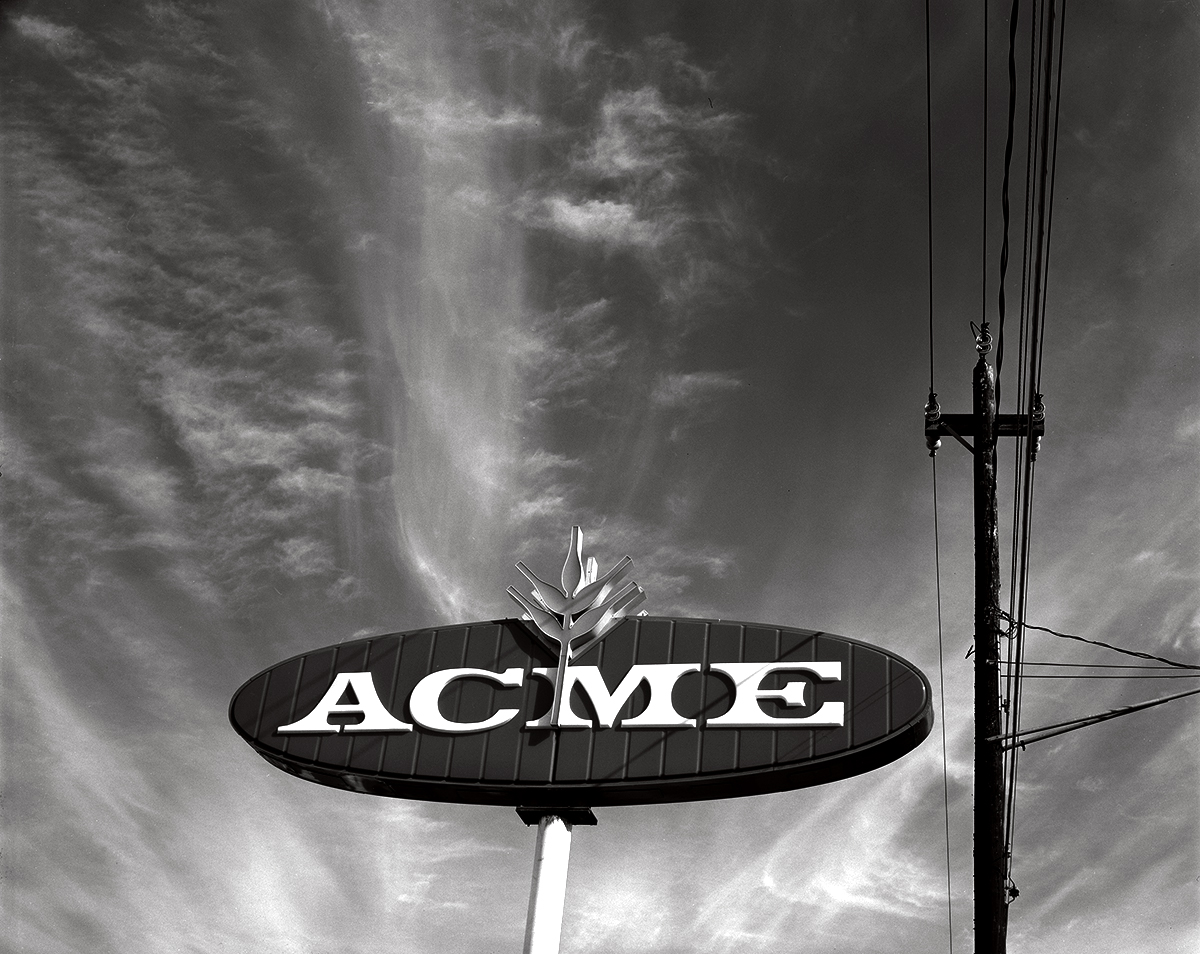

Wow. What a good question. When I began my search, there was not much available in my hometown of Akron, Ohio. Buddhism had not yet penetrated into the western mind. Carlos Castaneda had not yet published his first book, and the human potential movement was comprised of individuals like Krishnamurti, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Alan Ginsberg, and the followers of Jung. These people were unapproachable to me. They lived in the other side of the country or world, and their ideas did not impinge on my middle class existence of suburbs, hamburger joints, and leave-it-to-Beaver neighborhoods. I grew up with drive-ins, shopping malls, and corner ice-cream shops. Spiritual ideas were esoteric and inaccessible. But art was not. My teachers and peers engaged the creative process with the reverence and earnestness of a genuine search for being, for expanded awareness and consciousness. This touched something in me and awakened dormant longings for the miraculous, or something sacred that I sensed at the core of existence.

Wow. What a good question. When I began my search, there was not much available in my hometown of Akron, Ohio. Buddhism had not yet penetrated into the western mind. Carlos Castaneda had not yet published his first book, and the human potential movement was comprised of individuals like Krishnamurti, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Alan Ginsberg, and the followers of Jung. These people were unapproachable to me. They lived in the other side of the country or world, and their ideas did not impinge on my middle class existence of suburbs, hamburger joints, and leave-it-to-Beaver neighborhoods. I grew up with drive-ins, shopping malls, and corner ice-cream shops. Spiritual ideas were esoteric and inaccessible. But art was not. My teachers and peers engaged the creative process with the reverence and earnestness of a genuine search for being, for expanded awareness and consciousness. This touched something in me and awakened dormant longings for the miraculous, or something sacred that I sensed at the core of existence.

Now we have gone to the other extreme. The smorgasbord of spiritual teachings that are readily available is a good thing. Many living teachers make their ideas readily accessible through books, lectures, workshops, sittings, and more. Those individuals who are earnestly seeking may find teachings and teachers who can help them realize their aims. However, the clear danger, as I see it, is the phenomenon of what I would call, “a little here and a little there”, where people pick and choose among pieces of real traditions that suit their personality or their ego, not necessarily their essence. A real teaching is organic; one part is intricately connected to all the other parts. And a real teaching contains methods and means of growth that often go against the dictates of the ego. We cannot assemble a spiritual teaching to suit our whims or superficial desires. And, often, this patchwork quilt of particular lessons from the great traditions takes place under the misleading phrase, “seeking my own truth.” Well, I suppose I want to ask the question: If it is truth, how is it only your own? Truth is truth, and the first step on any spiritual path is finding the truth about oneself, the actuality of our present condition, which is often one of fragmentation and disassociation. We are not whole. We are not present most of the time. Yet, the very recognition of that fact is highly positive. Seeing the truth of what is, of our present condition, is the first step on the spiritual path in most of today’s traditions.

The action of seeing what is can change us, if we allow it to act on us. And the power to change the world can only begin from seeing what is, the truth about our condition as individuals and as a culture. There is great hope in seeing. As Alfred Stieglitz once said: “In one’s way of seeing lies ones way of action.” Awakening is paradoxical. The metaphor of diamonds and rust is an apt description of the spiritual path. Through seeing and accepting the rust, we may find the diamond. In the marvelous novel Mount Analogue by René Daumal, about climbing the mythical mountain that represents the spiritual quest, a group of intrepid seekers begin the ascent. Their leader, a Father Sogol, came to a sharp realization. He said something like: “far within me, where the memory of what I am is still unclouded, a little child is waking up, making an old man’s mask weep.” At that moment of recognition of truth, he looks to the ground and finds a peradam, a diamond-like crystal which is a symbol of our lucid moments of spiritual clarity and understanding.

The ascent of Mount Analogue takes place with others, of differing skills and specialties. More than anything we need each other. I am a seeker in the company of other seekers, some of whom have more experience than I, and some with less. And we need guides who are a little farther along the path than we are. The “teacher” can arise in the space where we work together. Something can descend, a kind of spiritual intelligence, when two or more are gathered together sharing the aim of inner evolution.