Reconciling the Dance of Opposites

Inner work is paradoxical. We are asked to delve fully into ourselves to see the shape of our inner being and the myriad manifestations of our conditioned selves. Yet we are asked to transcend ourselves and the unconscious, habituated parts of our nature. We need both discipline and surrender, assertion and receptivity. We are guided by the force of great ideas, but growth of awareness moves beyond word and concepts. In search of knowledge, we stand in front of the question facing the unknown and the unknowable. F. Scott Fitzgerald once said that the sign of true intelligence is the ability to entertain opposing ideas in the mind simultaneously. If this is true, then perhaps the mark of a truly creative individual is the ability to embrace and integrate what are often opposing forces and influences.apparently we believe

in the words

and through them

but we long beyond them

for what is unseen

what remains out of reach

—W.S. Merwin, from The Shadow of Sirius

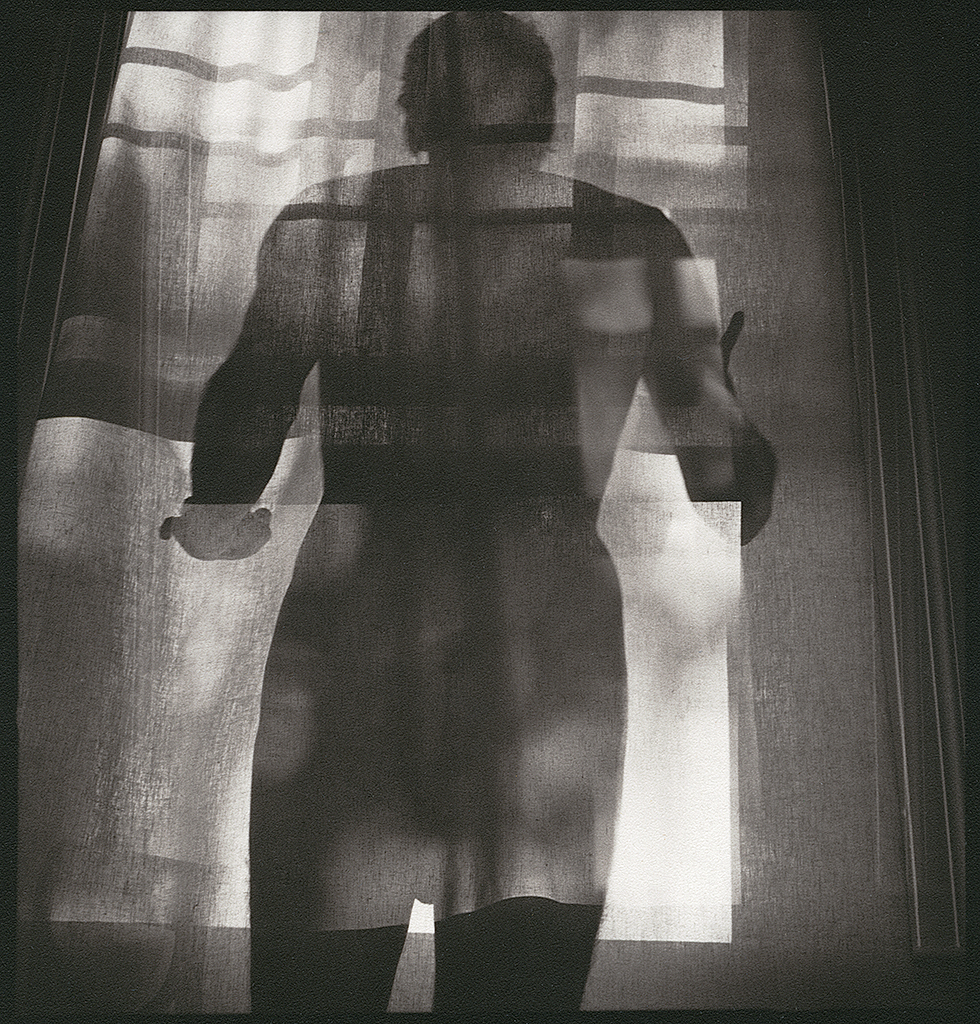

At a recent poetry reading, Poet Laureate W.S. Merwin asked the audience: Are you afraid of the dark? His question sparked an inward silence amongst those present due to the sincerity and earnestness with which it was asked. He continued by asking us to retrieve our memories of childhood, to admit to our awe in front of the unknown and the fear that it causes. Looking at the night sky, the poet claims, the universe is vastly dark, punctuated by light of the suns and stars. He writes: “Sometimes, at night, I turn on the light to not see my own darkness.” Isn’t this like us, and how we face the unknown? Our worlds dark and our minds ignorant, we stand with humility in front of what we do not and cannot know. Yet, the light beckons and brings joys and sorrows and understandings and sharp insights into the dark places.

Light and dark, higher and lower, good and evil, known and unknown: our rational forms of thought see the world as consisting of opposing forces. So much of life is lived on the periphery—right or wrong, male or female, black or white. Where do polarities intersect? What power brings dual forces together? We categorize and dichotomize, and in doing so, we deny the wholeness of ourselves. What can reconcile the dance of opposites? Perhaps it is in the reconciliation of opposites where true presence appears.

Poet Rainer Maria Rilke writes:

To work with Things in the indescribable

relationship is not too hard for us;

the pattern grows more intricate and subtle,

and being swept along is not enough.

Take your practiced powers and stretch them out

until they span the chasm between two? contradictions… For the god

wants to know himself in you.

Human beings stand potentially at the intersection of forces, from different levels and orders, interweaving within us, creating a bridge between the lower and the higher, the known and unknown. We know well the state of “being swept along.” From birth to death, we are inexorably and mechanically drawn into the forces of life. We live, work, play, come together and move apart governed by mechanical and often unconscious impulses. Yet individual human evolution is possible. The search for consciousness must make itself known in us. We must heed the call. If we wish to serve something higher than our conditioned personalities, we need to turn and face the great unknown, the search for Self and for hints of the divine order. Our inner work—efforts towards presence and consciousness—is the force that alone can lead us toward spanning the chasm of our contradictions.

We may look to the poets for not only helping us understand non-dual thought but how to live it; to find in our inner work the place that stands between, that blends darkness and light and integrates our human and divine natures. The great religious texts were often written in poetic verse: The Bhavagad Gita (The Song of God), the Psalms of the Bible. Indeed, even the concise declarative yoga sutras of Patanjali form a kind of poetry. Great poems can function as wisdom teachings. Take for instance the inspired words in Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman and the poetry of Rilke and Rumi. Their metaphor, myth, and symbol have the capacity to touch our Being and help awaken us to a form of thought that transcends the lower, rational mind. These poets beseechingly beckon us into their exalted world of union with the mysterium tremendum, or the overwhelming mystery of the numinous.

Sing in me, O Muse, and through me

begins Homer in the Odyssey.

You that sang to me once sing to me now

begins W. S. Merwin in the The Shadow of Sirius, winner of the 2009 Pulitzer prize for poetry.

The best poems are often oracular, arising from sources deeply unknown—that often come as a surprise even to the poet. They serve to teach, inspire, and delight the reader. As a poet matures, we find reconciliation and the cultivation of a perspective that transcends duality and linear based thinking, often vibrating in the mysterious field of discovery between the known and unknown.

Walt Whitman sings:

Clear and sweet is my soul, and clear and sweet is all that is not my soul.

Lack one lacks both, and the unseen is proved by the seen,

Till that becomes unseen and receives proof in its turn.

The gate to the unseen is through the seen. We begin with what we know yet the aim is to penetrate into the mystery. In this way, authentic teachings reveal themselves through the play of opposites, an opening to a fundamental paradox that begs us to ask the question “why?” We see duality all around us. Timeless teachings —Buddhism, Gurdjieff, Taoism, Yoga, and some forms of Christianity— point us in the direction of integration and unity, rather than separation and disparity. Yet they exist in a world built upon contrasting tenets. And indeed we see that much of spiritual practice today is performed as a means of self-improvement rather than self-awareness. and more often it is ego-driven rather than a coming together. We attempt to be more of everything. We live in a society of superlatives—thinner, smarter, richer, best—there is an incessant striving outward to become something other than what we are. How do we continue to keep our inner and outer lives in attunement with the essence of the non-dual teachings of all great traditions?

In The Bhavagad Gita, Krishna counsels Arjuna:

He who can see inaction

in the midst of action, and action

in the midst of inaction, is wise

and can act in the spirit of yoga.

A real teaching has embedded in it the potential for integration. We attempt to rectify the dance of duality in life, creativity, and spiritual practice. We strive to bring together the fragments of ourselves so that we may truly know what it feels like to be whole and integrated human beings.

In yoga, for instance, we attempt to cultivate an awareness of and integration of the Seer with what is seen and find a balance between commitment and non-attachment. The yoga practitioner holds the potential to resolve the contradictions inherent in bringing the mind’s intent to the earthly body. Standing between two mirrors we reflect between inner and outer, the mundane and transcendent, and the known and the unknown with an attention that reflects steadiness and ease. In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali says: Tato dvandva-anabhighatah. (2.48), Then one is no longer assailed by opposing dualities.

Ravi Ravindara elaborates on the balance between effort and opening: “Soon the need to act as a warrior gives way to the possibility of becoming a lover who is naturally interested in the connection with the subtler energies. When there is a right alignment with the Infinite, it is possible to let go of all effort, all struggle, and all tension. Then even the image of a lover is no longer relevant; the searcher is now like the beloved who is embraced by the lover who was earlier longed for. In this union, there is longer any struggle between opposites, between above and below, between lover and beloved. Not only is there physical relaxation, but also an emotional and mental reconciliation of dualities.”

P. D. Ouspensky, in his book on the Gurdjieff teaching, In Search of the Miraculous, speaks of the need and the means through which we may reconcile duality. Action opposes inertia. Thoughts can oppose feelings. Conscious intent opposes mechanicality. For this condition to change, a trinity must be established. The third force in relation to work on oneself then might be appearance of new knowledge, or contact with a teaching that shows the means and methods of inner work towards a desired result. Or the third force may be found through impartial self-observation. If we can see and honestly accept our automatic manifestations then we are already in a state of greater consciousness. We see the truth of our condition. The great chink in the armor of our mechanicalness, according to Ouspensky, is the experiential realization that we are not conscious, that we do not “remember ourselves.” “By realizing all that this means—this will bring us to consciousness.” Simply seeing the darkness is itself a form of illumination.

Walt Whitman writes: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” Accepting the paradoxical condition of what we are, and both recognizing and accepting the largesse of our humanity begins the process of reconciliation between the darkness and the light—in oneself.

In a PBS interview with Bill Moyers, W.S. Merwin states: “We are the shadow of Sirius.… As we talk to each other, we see the light, and we see these faces, but we know that behind that, there’s the other side, which we never know. And that — it’s the dark, the unknown side that guides us, and that is part of our lives all the time.”

“I think that poetry and the most valuable things in our lives … come out of what we don’t know. They don’t come out of what we do know. They come out of what we do know, but what we do know doesn’t make them. The real source of them is beyond that. It’s something we don’t know. They arise by themselves. And that’s a process that we never understand. … finally your thought comes to an end. It’s lost in the what we don’t know and the vast emptiness and unknown of the universe.”

In our most profound moments—of beauty and radiance, of great pain or trauma, of love and awakening, of seeing and feeling the sublime—we also sense our mortality. Everything that is born must die. All the manifestations of life that we are privileged to experience are temporal and mortal, and will pass from this earth. The Greeks have a word for this: pathos, which, in our view, represents the duality present in rare moments of awareness when joy is intertwined with sadness, and hope is tempered by reality. Pathos, we believe, is seen in many works of art where we feel simultaneously a living, radiant presence combined with a recognition of the sometimes painfully acknowledged facts of our existence. Indeed, in many of the greatest works we find a search for wholeness of spirit, for redemption, and for eternal values expressed through the transitory moments and ephemeral circumstances of our lives. Merwin’s mature poetry, Rilke’s later work, the Sonnets to Orpheus and the Duino Elegies, all contain this admixture of joy and sadness, this tempering of darkness with transcendent light, and express in Theodore Roethke’s words “The intolerable sadness that comes when we are aware at last of our own destiny.”

Whatever Roethke may be referring to in his personal destiny, we cannot know. But it is in our lot as human beings to maintain this tenuous balance between the unrestrained joy of being alive, with the absolute certainty that we, like all things, will someday die—and that our lives on this planet are temporal and short.

This quality of pathos may very well be the source of the phrases: struck by awe or wounded by beauty. Awakening exacts a price, and real seeing acknowledges both: the life force present in all things and the concrete realities of living and dying. It acknowledges our highest and best possibilities as well as our most conflicting elements and greatest obstacles.

For me the world is weird because it is stupendous, awesome, mysterious, unfathomable; my interest has been to convince you that you must assume responsibility for being here, in this marvelous desert, in this marvelous time. I wanted to convince you that you must learn to make every act count, since you are going to be here for only a short while; in fact, too short for witnessing all the marvels of it.

—Don Juan, as told by Carlos Castaneda