Digital Technology and the Search for Meaning

I admit it. I love electronics. I am one of those that frequent the Apple store during the launch day of new products, as I did with the new iPhone and iPad. I prefer writing on a keyboard and monitor, watching the words flow across the screen seamlessly tethered to my brain. I love working with images on the computer; the speed, flexibility and power. When many ask if I miss the alchemy of the darkroom, I answer, why? There is a different form of alchemy – more immediate and more streamlined – that can be found and experienced in digital processes. Also, I spent thirty years in the dark, inhaling noxious fumes in a photographic darkroom and spending endless hours washing and toning prints from a day of work to insure archival longevity. Now I prefer the light, both physically and metaphorically. And I prefer speed and lightness of performance.I have often questioned why technology is so seductive and, for me, enjoyable. Is it merely another form of attachment and identification that provides escape and a strong mechanical, involutionary force that pulls me away from the emergence of my real self? Maybe. Many would say that is true. The seduction of technology and social media can be an enormously powerful distraction, fragmenting my attention even more than is customary for me. And it can lead me away from the genuine presence of residing in the body, opening to feeling and to the depth mind. Many social critics have made the assertion that today’s technology fragments our attention span, increases our isolation from others, and offers shallow gratification in place of genuine openness to ourselves and each other.

But I feel strongly there is another side to this question. Anything that we become attached to or identified with often contains rich substance and great energy for our being. The problem is: we misuse it. We abuse it. The powerful energy found in our attachments can be liberated and released if we can learn to work with the siren call of these outer attractions. Can we stay mindfully in touch with our being in the midst of these compelling shiny objects? When I first encountered computers in the 1980’s, I refused to own one or even work on one. I found them to be profoundly dehumanizing. Any computer work that needed to be done for my job I gave to my assistant for implementation. Out of sight; out of mind. I viewed the emergence of the digital world as a nightmare for our humanity, a dark night of the soul for our inner worlds and varied social interactions.

Now I see it differently. I could not initially understand why digital devices are so satisfying on some internal level. As soon as I began to work on a computer, I found a powerful and, at first, strange connection to my inner world. I have always valued artistic tools and how they extend human functions. The camera is an extension of the eye and the brain. The paintbrush is a metaphor for the hand and eye of the artist. And the potter’s wheel reflects one’s physical being and asks for a centered presence of the human body. These tools are metaphors for human capacities. Suddenly, I realized: the computer is a metaphor for the human nervous system. The stimulations, connections and synapses of the brain are mirrored by digital technology. Our own centered presence, or lack thereof, is often reflected by the devices we interact with.

We have an electrical field in our bodies and minds. Our being has vibrational substance and materiality. Science is now able to precisely locate where certain stimulations touch the brain and how emotions and states of mind have measurable psycho-chemical properties. What science is slowly proving has been known to inner researchers for hundreds of years: that meditation and inner practice can physically change our brain waves, emotions, perceptions, and emanations.

When cell phones were introduced into common usage a decade ago, I marveled at how this miniature device could pull invisible signals from the air and transform them into pictures and language, either spoken or written. We have the same sort of inner antennae, capable of receiving and transmitting subtle signals, to and from the atmosphere surrounding us. Apart from potential health dangers of radiation or signals from our devices, a profound metaphor is at work here. The electrical field of the human body can be affected and modified through meditation and contemplative practice to become more receptive and attuned to sources of subtle wisdom. When the nature of our inner energies, our electrical field, uplift as it were, we can touch sources of inner wisdom and forms of knowing that extend beyond the rational brain. We attune ourselves to open to the vibrating silence and what it may contain as a greater intelligence. We can refine our frequency of vibration to hear the call of invisible energies that lie within us and around us, similar to the manner in which a cell phone receives invisible signals from the air itself. Many questions arise here that can nourish our search for wisdom and inner evolution.

The other side is true also. I have verified time and again in teaching digital technologies that the nature and quality of one’s nervous system can affect the electronic devices around us. People’s energies affect electronics and visa versa. The quality of our internal energies emanate outward and affect the electronic devices around us. And conversely, our devices affect us. Can this be transformed into a positive, life enhancing experience?

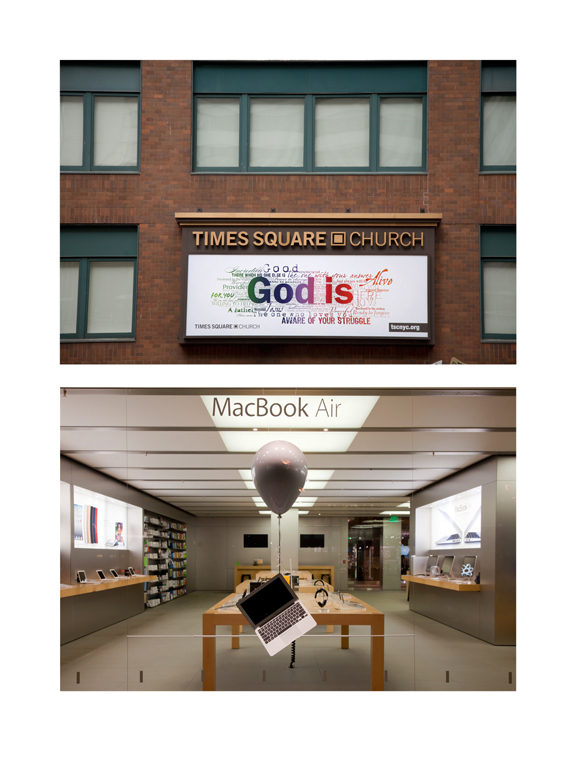

A study in the UK commissioned a team of neuroscientists to employ a MRI scanner to examine the brains of fervent Apple computer fans. The BBC reported: “The results suggested that Apple was actually stimulating the same parts of the brain as religious imagery does in people of faith.” Our quest for and use of the newest, greatest digital device touches the same places in the brain as the religious impulse, the search for meaning and greater dimension to our lives. Even Pope Benedict XVI acknowledged this fact in saying that “technology consumption poses a threat to religion and the Roman Catholic church.” The holy leader taught in a Palm Sunday sermon that “technology cannot replace God.”

At their best, these tools offer a new form of craft that can, when used correctly, deeply engage our inner energies and creativity. When writer Natalie Goldberg asks her teacher Dainin Katagiri Roshi about Buddhism and sitting, he answered: “Why don’t you making writing your practice. If you go deep enough into writing, it will take you everywhere.” We need to learn to use the things we care about and disentangle our identifications so we can sit in front of our attachments with a freer attention and an openness to receiving and eventually even transforming their charged energy.

When I sit down at the computer to write or work with images, I now try to remember to take this time to engage my body, to breathe, to seek an attentive presence, and to observe the myriad of thoughts and feelings that inevitably arise. I can’t say I’m good at it, but, since I spend so much time in front of a digital screen, it has become a touchstone for me, a time and place to encounter myself in all of my splendor, terror, and glory. In the end, technology is just a tool, a powerful one that can open us and unite us, or fragment and enslave us.

Victor Hugo worried that “This will kill that,” referring to a machine-printed book compared to the pristine architecture of Notre Dame. Hugo believed that before the printing press, humanity communicated its deepest truths through architecture. The gothic cathedrals, according to Hugo, reached the pinnacle of expression through “books of stone,” giving flight to the human spirit through careful use of space, light, symbol, and proportion. I personally don’t think books fared so badly over the years. Nor did they kill architecture or any other form of human creative expression. Now many worry that this, the digital machine, will kill that, the spoken and written word as well as the analog image. It all depends on us.

Electronic technology is ours. It was born in our time. I remember the first TV set replacing the radio in the living room that my parents and grandparents would gather around. We stand on the edge of a world both enhanced and disrupted by digital technology. How will we use it? Can it continue to evolve as a profound tool for creativity and deep, human communication? Can it serve our inner quest for meaning and consciousness, and the expression of that search? Or we will we allow its use to be subsumed by consumer culture and its dehumanizing attitudes that fracture our attention and isolate us from a true connection with each other. We need to face these questions together, as individuals and as a collective. The turning point is here . . . now. What will we serve and which way will we turn?