The Search for Clarity and Wisdom

In the last five minutes of a free public critique of photographs, a person asked me about whether we can trust the responses of others. We come (especially in Hawai‘i) from differing cultural backgrounds, experiences, and circumstances. Don’t we bring our own baggage to a response, any response? Can we actually believe that someone is talking about the work, or merely themselves?I answered him by saying that I couldn’t answer him, that the questions he raised take a lifetime to explore and untangle. However, the language of art is something we can talk about, evaluate, and judge. How the individual uses the visual language of form, shape, line, composition, color, and overall technique is quantifiable. How these elements are used to express the intended content can be evaluated. In my experience, another condition persists, and I’ve noticed it for in the classroom for thirty-five years now. If we imagine an artwork at the center of a circle and a number of individuals placed around the circle, I have found consistently that, though individual responses differ based on the subjectivity of the viewer, they generally all revolve around a single point. In other words, they often say similar things in response, though the words and particularities, what they emphasize or focus on, is different. It’s quite remarkable and suggests that something consistent is expressed to everyone in the room. Now this all works largely because we are from similar cultural backgrounds, i.e modern culture. If we showed the image to a native of the Borneo jungle, it would admittedly generate a widely different response.

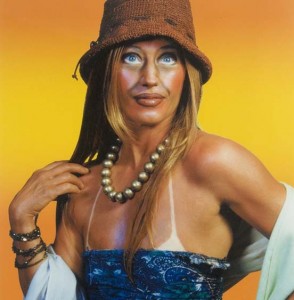

© Cindy Sherman. Sherman’s photographs represent a constructed, cultural identity, from a feminist perspective, exploring the roles women play in society through elaborate costumed, self-portraits.

What is art? Is it all subjective or is there the potential for a universal language embedded in artistic expression? I want to express myselfis the cry of the artist. But what self? For an emotional person, art often serves as catharsis. For a thinking person, art becomes conceptual, an exploration of ideas. For the highly physical, sense oriented individual, the craft of making things, the striving towards excellence, becomes a dominant goal. For feminists or Marxists, the relativity of expression based on cultural standards, ethnicity, gender, economic status or class, holds the larger truths, with the aim of representation of one’s identity. All of these modes of expression are valid and valuable, but remain partial and incomplete.

Another possibility can be found in great art—that art is, or can be, an expression of the potential wholeness of the human being which can integrate the intelligence of the mind, the sensitivity of the feelings, and the wisdom of the body, without denying or promoting its underlying cultural basis. Art is born of the times, generated from the enduring labor of a specific individual, yet can contain universal and timeless themes and perceptions. Many researchers acknowledge that the deeper levels of our human potential are not strictly individual; rather they arise from a knowing that transcends the ego and the self. In great art, we are witnessing the reflection of a grown-up individuality. In becoming more of oneself, who we really are, we are reaching the depths of the human condition. In these instances, art grows from the perception of awakening individuals.

Chogyäm Trungpa has observed: Perception can be categorized into three levels: experience, emptiness, and luminosity. At the fist level, experience, perception … is the experience of things as they are. … You actually experience something as through you were it. You and the experience become almost indivisible … It’s that kind of direct communication without anything in between.

At the third level … we have a sense of clarity and a sense of things as they are seen as they are, unmistakably.”

Can we then measure art by the consciousness of its maker, reflected and embodied in the work? Certain works of art arise from somewhere else, not the ego or the mind or the reactive emotions. Artists are informed from a place that we cannot know: the unconscious, a spiritual intelligence, a natural clarity of the mind and being.

Artists can get to a stage where the ego becomes transparent, where the beauty and elegance—or suffering—of the world speaks through them. The work becomes a reflection of a search for consciousness. This is not uncommon in the annals of art, even modern art. Look at Mark Rothko’s stunning large canvases of luminosity and color that transcend opinion and mere thought, and awaken awe in the face of the sublime. The mature work of Mark Rothko is, according to Roger Lipsey, “one of the great spiritual realizations of twentieth-century art in any medium.” Rothko’s own statements confirm his artistic intent: “I don’t express myself in painting. I express my not-self. The dictum know thyself is only valuable if the ego is removed from the process in the search for truth. Art is not self-expression as I thought in my youth… a work of art is another thing.” In a visit with a friend, the art critic Dore Ashton, Rothko asserted “They are not pictures.”

Lipsey referred to them as “the silence and solitude of consciousness.” Another perceptively commented that they are like “silence bursting outward.”

What then is the measure of a work of art? By what means do we evaluate art or respond to individual works? This is a shifting point for most of us, an unfolding matrix based on our level of understanding and where we find ourselves at a given moment. In his book, In Search of the Miraculous, P.D. Ouspensky quotes G.I. Gurdjieff: “You must first of all remember that there are two kinds of art, one quite different than the other — objective art and subjective art. All that you know, all that you call art, is subjective art, that is, something that I do not call art at all because it is only objective art that I call art…. We have different standards. I measure the merit of art by its consciousness and you measure it by its unconsciousness.”

As a student of Gurdjieff’s ideas, I have struggled to understand this division of art into objective and subjective. I have often cast a negative light on the concept of subjective art, while, at the same time, recognized that objective art was beyond my grasp. Isn’t subjective art useful, perhaps integral, for the inner development of the artist? We express ourselves in order to see and know ourselves, and in order to make the contents of our unconscious more conscious—to bring the material of our unconscious into the light. And in this form of self-expression, we invite others to participate in the process of our discoveries and realizations. Subjective art leads toward consciousness if approached rightly.

Perhaps we can view this division of subjective versus objective art as an axis, a continuum, where works of art, and our own creative efforts, are located somewhere on a scale between consciousness and unconsciousness. Ideally, through our works of art, we strive toward consciousness. And we instantly recognize that certain works arise from a greater consciousness; and further, that these works have the capacity to deeply nourish, to inspire, to teach, to uplift our earth-bound nature to a higher dimension. Many works indeed express the art of becoming conscious.

Certain works of art and literature have the capacity to embed themselves in our consciousness because they are already there. The artwork embodies an archetype that we know and identify within, in the unconscious: Homer’s evocation of Odysseus’s journey reflects the heroic encounter, the hero’s journey. Similarly in Rothko’s paintings, individuals engaged in meditative practice can recognize the truth embodied in his work and how it mirrors inner states of luminosity and clarity.

Response to a work of art is a living exchange between the artist and their muse, and the audience. A response to a work can be creative and thoughtful, innovative, and inspirational. We can strive towards a perception that includes the clarity of the mind, the wisdom of the body and senses, and the refined sensitivity of feeling. The meaning of art lies somewhere in the space between creation and reception, between artist and audience, between consciousness and mind, feeling and body. Art can teach us about our humanity, and our responses to art can teach us something about our selves and the work of art simultaneously.

Alva Noë writes in the New York Times on Art and Limits of Neuroscience. “It is people, not their brains, that make and enjoy art. You are not your brain, you are a living human being.

Some of us might wonder whether the relevant question is how we perceive works of art, anyway. What we ought to be asking is: Why do we value some works as art? Why do they move us? Why does art matter?

Art, even for those who make it and love it, is always a question, a problem for itself. What is art? The question must arise, but it allows no definitive answer.

… It may be that art, by disclosing the ways in which human experience in general is something we enact together, in exchange, may provide new resources for shaping a more plausible, more empirically rigorous, account of our human nature.”

Sometimes with nature or with art, you experience greater insight, a real moment of enlightenment, or a luminosity that connects you with the world or nature or others. By understanding the nature of your own mind, you naturally come to what we call intuition and insight. These moments come from your practice, from developing loving kindness and compassion, and they are moments of what I would all genuine wisdom.

—Matthieu Ricard, in an interview with the author