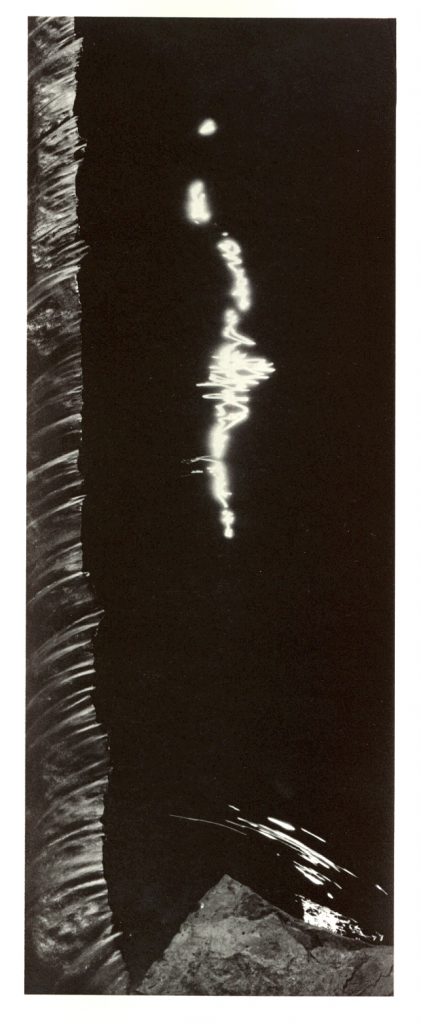

Easter Sunday, Stony Brook State Park, New York, 1963 by Minor White

The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White © Trustees of Princeton University

Natalie Goldberg, author of the excellent book, Writing Down the Bones, uses writing as her practice to stimulate creativity and “become sane.” Her Zen teacher, Dainin Katagari Roshi, said to her, “Why don’t you make writing your practice? If you go deep enough in writing, it will take you everyplace.” Taking delight in not knowing, embracing questions and discovery, and seeking the still point at the center of the wheel of action are fundamental qualities shared by both the artist and seeker.

Creativity is not just an inborn trait; it is available to everyone. Picasso said, in an oft-repeated quote, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” To understand creativity, we need to get closer to its source by examining the traits that decidedly creative people have in common. Theories of creativity abound. There are many ideas of what it means to be creative, and many of those ideas closely align with Zen practice.

Let’s look to one of the experts, the psychologist best-known for his studies of the creative individual. Psychology professor Mihaly Csikszentmiahli (MC) is the founder and co-director of the Quality of Life Research Center at Claremont College and has made an extensive study of creativity over much of his long career. In his book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, he interviewed 91 exceptionally creative people. These individuals were all internationally recognized for their work as physicists and biologists, politicians and business leaders, poets and artists. Derived from the interviews and from 30 years of research, MC uncovers and clearly delineates ten distinctive attributes shared by highly creative people. He describes these attributes as paradoxical pairs. “If I had to express in one word what makes their personalities different from others, it’s complexity. They show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segregated. They contain contradictory extremes; instead of being an ‘individual,’ each of them is a ‘multitude.’”

Zen practice shares, and even surpasses, the panoply of joys, challenges, and discoveries available through creativity. Your creative efforts usually result in some form of manifestation or object: a poem, play, painting, new product, or photograph. In Zen, you work on enlightening yourself. The journey is both celestial and personal. It moves to farthest reaches of the stars and deep within the recesses of the mind. It is noteworthy that some of the same traits of highly creative individuals can be found in the antithetical pairs of concepts at the heart of Zen teachings that practitioners strive to integrate and embody. Paradox is inherent in the creative process, and in Zen. Opposing characteristics can be embraced simultaneously and reconciled, helping us become more fully human.

These ten antithetical traits, which I am paraphrasing here, are often found in creative people and “integrated with each other in a dialectical tension,” according to MC. I have placed Zen concepts in italics before the traits of creative people. They are remarkably similar.

1. Stillness in Movement. Highly creative people are intensely alive with an abundance of physical energy and a healthy dose of eros—and they seek stillness and quiet. They alternate enthusiasm and great concentration with periods of solitude for rest, reflection, and incubation. They are highly motivated yet need to withdraw periodically to tap their sources of insight and inspiration. They often seek the still point at the center of the wheel of action and exercise some form of contemplative practice.

2. Intelligence and No Mind. They are smart and manifest a general or specific intelligence, such as verbal, spatial, or musical, yet are open to new impressions and ideas. They are divergent thinkers, able to live with ambiguity and not-knowing while they follow a meandering, developing process, switch perspectives, and connect disparate ideas. In this sense, creativity is combinatorial, taking ideas from multiple sources and synthesizing them into meaningful patterns or new conditions.

3. Single-Pointed Focus and Expansive Awareness. Creative people combine playfulness and focus. They have inquisitive minds, are highly curious and experimental, and entertain “wild germs of ideas,” according to MC. This balance between freedom and discipline is the mark of a great artist or scientist. Their minds soar while their working habits involve perseverance, rugged endurance, and the willingness to work things through no matter what the level of difficulty. They bring a high degree of focused attention to their tasks yet allow their minds to wander in fruitful directions.

4. Discernment and Acceptance, Seeing What Is. The artist or scientist savors their fantasies and leaps of imagination, stays open to the guiding visions and voices of the muse, their sources of inspiration, yet they are firmly rooted in reality. Their vision is often ahead of their time, their inspiration and winged thoughts relate to the future and what can be, yet they are fully in touch with the needs and demands of the present.

5. Inwardness and Living in the World. Self Awareness and Cultivating Empathy and Compassion. Creative individuals look outward and inward simultaneously. They can be both introverted and extroverted at the same time, or alternate between these differing poles of experience in response to different conditions. They have a high degree of self awareness and a passion for full engagement with the world. Contrary to the popular beliefs about the isolation of artist, most of them are acutely aware of the times in which they live and draw their ideas from both inner, lived experiences and outer, societal conditions.

6. Natural Wisdom and Beginner’s Mind. Highly creative people exhibit a natural confidence, yet have earned deep humility. They are proud and can place their accomplishments in perspective, knowing their own value but respecting their place in a long line of other contributors in their field. They believe in themselves but understand that their insights and works are not for themselves alone. They bow to their sources of inspiration, from the deeper mind, and have humble respect for the integrity of the creative process. To them, the first step of wisdom is the recognition of their own ignorance. They delight in not-knowing and in seeing the shape of the mountains of discovery that lie ahead.

7. Assertion and Surrender. They escape rigid gender stereotypes and are likely to manifest a combination of traits that are traditionally perceived as masculine and feminine. According to MC, they can be psychologically androgynous, having the strengths and attributes of both genders. They can be assertive and receptive, tough and vulnerable, sensitive and strong, all at the same time.

8. Free Spiritedness and Discipline. Creative types can be both rebellious and conservative. They rebel against outworn standards and sloppy thinking yet respect the traditions of their domain. They have nerve and are willing to take risks—to break the mold—but understand that novelty for its own sake is rarely a solution or improvement. They disrupt existing conditions but do so for the betterment of society. They are radical and challenge the status quo but still do their laundry, pay their bills, and meet their commitments. They seek the flame of insight but still pick up their kids from soccer practice.

9. Doing and Not Doing, Effortless Action. Highly creative people engage their work with a great deal of passion—and a healthy sense of detachment. Passion sustains interest and commitment to the task, and critical discernment helps in knowing the strengths and shortcomings of the developing piece. They strive to see things as they are and have objectivity. They aim for a full engagement in the creative process and non-attachment to the result.

10. Presence and Emptiness. The openness and sensitivity of creative people can invite a sense of joie de vivre and bring a great deal of enjoyment, along with both suffering and pain. They feel deeply and take life in large bites. They care about making a difference and are disappointed when on the sidelines. Creative individuals may feel isolated and misunderstood as their interests and views differ from the majority.

MC writes: “Perhaps the most difficult thing for creative individuals to bear is the sense of loss and emptiness they experience when, for some reason, they cannot work. Yet when a person is working in the area of his of her expertise, worries and cares fall away, replaced by a sense of bliss. Perhaps the most important quality, the one that is most consistently present in all creative individuals, is the ability to enjoy the process of creation for its own sake.”

Creativity is a peak experience. The same highs are experienced with the creative process as, say, in falling in love or traveling to new and exciting places. The same insuperable challenges are found in being creative as are found anywhere in the human condition. Surmounting these obstacles and approaching your own creativity unreservedly is one of the most fulfilling and demanding human experiences, one that can help make you whole.

These attributes related to Zen and creativity are explored in my new book Zen Camera. The book exemplifies the Zen-like finger pointing at the moon, offering a means of approaching your own creativity vigorously without knowing all the answers about the source and nature of creativity. In spite of the voluminous research on the topic, it remains a beautiful mystery. In Zen and the Art of Archery, Eugen Herrigel explains, “Bow and arrow are only a pretext for something that could just as well happen without them, only the way to a goal, not the goal itself.”

“Do you now understand,” the Master asked me one day after a particularly good shot, “what I mean by: “It shoots, It hits?”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand anything any more at all…Is it ‘I’ who draws the bow, or is it the bow that draws me into the state of highest tension? Do ‘I’ hit the goal, or does the goal hit me? Bow, arrow, goal and and ego, all melt into one another, so that I can no longer separate them. And even the need to separate is gone. For as soon as I take the bow and shoot, everything becomes so clear and straightforward and so ridiculously simple…”

“Now at last,” the Master broke in,

“The bowstring has cut right through you.”

Essay adapted from Zen Camera: Creative Awakening with a Daily Practice in Photography, forthcoming early 2018, Ten Speed Press/Random House. www.zen.camera

Essay adapted from Zen Camera: Creative Awakening with a Daily Practice in Photography, forthcoming early 2018, Ten Speed Press/Random House. www.zen.camera

Please follow my new Zen Camera Instagram feed: @zen.camera