Part One

As a spiritual seeker, and as a guide and mentor for some, I hold many questions about the state of spiritual practice in today’s world. Many authors and teachers have shared acute observations about the “flatlining” of modern society — that many don’t acknowledge any reality higher than what can be perceived directly by our senses or by the means of scientific inquiry. Myth and magic, religion and the soul are considered suspect as they cannot be proven or measured. We no longer have a god or a pantheon of gods we can call our own. Quite simply, the spiritual search has been brought down to the material level. Spirituality has become commodified and denigrated, echoing Chögyam Trungpa’s powerful phrase “spiritual materialism.” Once powerful teachings from all over the world have come to Western shores and mixed into the fabric of modern life. What takes place in that mixture? Can we begin to critically examine what is needed for teachings to remain alive and relevant? What is the obligation of the seeker, and what responsibilities are held by teachers or the teachings themselves? We intend to explore these questions in a series of essays, starting with a brief snapshot of the state of modern spiritual practice.One of the questions that spiritual teachings face is how to adapt to changing times without diluting the essential nature of the tradition. Nearly thirty years ago, at a weekend gathering devoted to inner work studying the Gurdjieff ideas, one of my primary teachers, D.M. Dooling, founding editor of Parabola magazine, presented the challenge. She spoke of one of the defining characteristics of society in the modern era; that in our quest for democracy and justice for all, we no longer honor the existence of forces, energies, and sources of wisdom higher than ourselves. We no longer believe in varying levels of existence and even differing levels of being amongst people. She said, and these words ring in my mind now as they did then: “It has not been my fate to deal with the inevitable dilution of these ideas during my lifetime.” Then she looked long and carefully at us and said, “It will be your fate.”

Spiritual work is beyond self-improvement

Now we see potent teachings being appropriated and brought down to the most common level — principally to serve illusions of the ego and the needs of the wordly self. People meditate merely to become free of stress and trauma, use powerful techniques of mindfulness for the lesser goals of finding relaxation and lowering blood pressure, and seek magical states through shamanistic rituals and drugs such as ayahuasca and ecstasy. In The Atlantic, Thomas Rocha writes: “Many people think of meditation only from the perspective of reducing stress and enhancing executive skills such as emotion regulation, attention, and so on.” And Joshua Eaton makes the comment in Salon: “Many Buddhists now fear their religion is turning into a designer drug for the elite.”

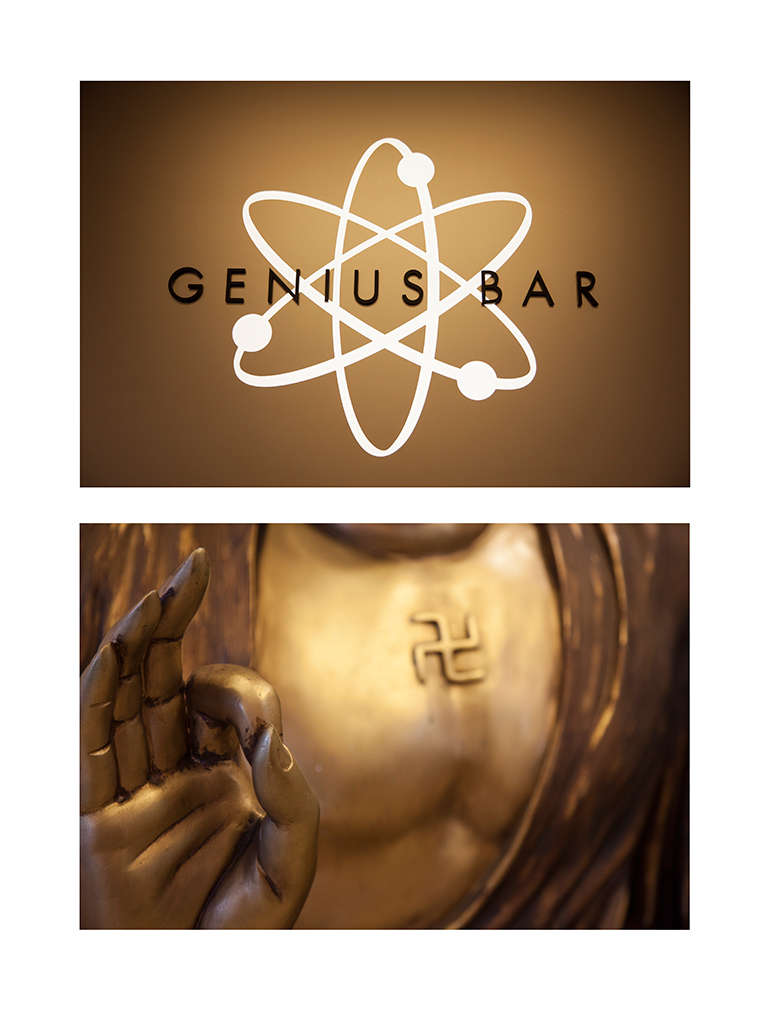

© David Ulrich. David’s current series of photographs explores how words and symbols that were once considered sacred or indicative of the higher reaches of human nature are now being appropriated and denigrated to the level of commercialism merely to sell consumer products. Apple computer, for example, regularly uses words such as genius, evangelist, and claim their computers can “paint like Kandinsky and play like Paderewski.”

And for the most part, yoga lost its soul in coming to the west. Yoga and pop-culture Buddhism have become the poster children of the compromised spiritual practice. Asana and meditation are practiced with the intent of looking and feeling fabulous. Even tenets like seva, or service, and metta, loving kindness are often promoted as a way to be a “better person” while taking little account of those who would be the rightful recipients of such “betterment.” In all of these instances, it’s all about me; it’s about my wish and my need to become a better person, to be loved and admired, and to become attractive, confident, and successful.

On one level, this is understandable. To seek health, happiness, and success and to strive towards excellence in our endeavors represent honorable and normal goals. Without this drive for self-improvement we would be ignoring the fundamental levels of our humanity. However, these goals only represent the very foundational levels of our human potential. We are meant to live in two worlds, to traverse the regions between the lower and the higher, to embrace both aspiration and inspiration.

Inner work is alchemical; its aim is a transformation of being, an uplifting of flesh and blood to the blood of Christ, to a consciousness is larger than we are — yet also exists within us. Self-improvement, as much it may be necessary, is not the proper aim of inner work. Mrs. Dooling would often ask: What serves what? Do we meditate, do yoga, and engage spiritual practices for the aim of becoming a better person, having an attractive body, or even for the development of the mind? The simple answer is no. It is not enough. We seek to transform the entire body-mind into light-giving, living energy, to transform negative emotion into faith, hope, and love, and to find an intelligence and quietness of mind that is sufficient to embrace and reflect the whole range of life’s manifestations.

Self-improvement is the precursor, a preparation for genuine spiritual practice. It is essential to have a relatively healthy psycho-physical-sexual integration of our lower nature before we can approach the great aim of transformation. Ironically, we need to build our ego to meet the demands of the world and to make it strong enough to let go, surrender, and relinquish its hold over us. We need to look within our own darkness and strive to heal the complexes and wounds from our childhood (or earlier) in order to create a solid foundation for growth. Without some form of therapeutic work, we risk imbalanced development. Power corrupts only when the ego is unhealthy and appropriates the legitimate gains we may make. We see ample evidence of this with the bedfellows of manipulation and power games leading to exploitation and abuse of the sincere seeker.

A genuine search is a call, often a whispered longing, from the deeper parts of our nature, calling us to become whole, to connect with the sources of wisdom and knowledge that lie covered over, unseen due to the dominance of our social and material selves.

What is integrity and can it be found in teachings today?

Laura and I, and others, have engaged in an ongoing dialogue about spirituality today and embarked on a study of the topic. Laura posed a few questions regarding inner work in the modern world to a group of ardent seekers and spiritual people of younger generations. Those questions included: Why have we committed to a real spiritual practice (that is not just self-improvement)? Why have we hesitated around such a commitment? Can you name what it is you practice in simple terms? And if not, how would you speak about it to someone who knew nothing about anything at all spiritual in this postmodern world?

Those who responded were fairly unanimous in their experience of the great difficulty of finding a genuine spiritual teacher. Furthermore, upon finding a teacher, people have recounted disillusionment from witnessing a lack of integrity or a wide gap between a teacher’s public face and their private activities, with criticisms such as self-absorption, selfishness, exploitation, and patriarchal attitudes.

Laura writes in response to her own inquiry: For a long while after starting a yoga practice I was on the hunt for a guru — a guide even, someone who might be able to help me understand some of the esoteric things I was exploring. I didn’t find anyone in the yoga scene, though the ashtanga practice has been a valid way to cultivate self-observation. The cycle I repeated followed a sequence of: idealism upon finding someone who might fit the “guru” category, tentative commitment, and disillusionment when my expectations were either not met or completely steamrolled with the emergence of inconsistencies between what is practiced and what is preached.

The question persists of what constitutes a real teacher? So many students come into yoga studios with a range of questions about their bodies, their minds, and their lives. Most every one of these questioning souls really wants answers. Yet, I find myself moving farther away from answers as a student and a teacher. The questions have become far more compelling.

About three years ago, I decided to take a look beyond postmodern yoga and cast a wider net. I revived my sitting practice and joined a weekly sitting group that also took the time to discuss ideas on inner work. For the first time in a long time, I felt transported and transformed. Thankfully so, since the spiritual plateau I had found myself on for the previous five years turned out to be flat prairie land.

As I looked beyond asanas and the body, and as my inner life grew richer, I stopped kicking up stones looking for “the One.” The people in my sitting group became a good sangha, when the yoga community had not provided the same support. I haven’t found “gurus” who know lots of esoteric things, but in their place I have discovered a world of guides and elders who have walked this path before me. I’ve met meditation teachers, philosophers, and spiritually minded elders who have not only made themselves available to me through face-to-face meetings, email and phone conversations, but also have allowed me to explore my questions with the knowledge that those questions will never cease. In doing so, they have given me great freedom to return to a state of innocent curiosity and enchantment with the inner world. You could say it’s like the gift that keeps on giving.

It’s a dangerous proposition in this day and age of spiritual materialism to encourage spiritual people in the Western world to “shop around,” but the unfortunate truth of the matter is that most of us have likely received second or third hand teachings that have already been “shopped around.”

We really have to employ the use of our whole selves when looking at a path. It’s okay to question a path, it’s okay to question your teachers, and every once in a while it’s okay to take a journey away from familiar territory to see what else is out there. Who knows what you might find. Commitment is unduly important. If a path strikes the right note it is important to take the leap. My admitted cynicism has served me well in protecting me from charlatans and whackos, but it’s done little in helping me look deep within. For that, I’ve needed to cultivate some degree of faith and trust of a teaching just as much as in a teacher.

What is my responsibility?

When we do find a meaningful path, we need to respect the integrity of teachings. Every genuine teaching — Buddhism, the Gurdjieff Work, Sufism, Esoteric Christianity, Native traditions, and others — forms an integral whole of theory and method, cosmology and stages of practice. They cannot be splintered without distortion and damage. The attitude of the spiritual eclectic often remains rooted in personal spiritual growth without considering the development of others or the impact on the teaching itself. Engagement in genuine spiritual teachings is equally for oneself, for others, and for the world itself. Indeed, the aim of one’s own enlightenment is no more important than the awakening of others and the healing of the world. Yoga teacher Michael Stone writes, “Mindfulness is… designed to reduce stress and suffering both in our own hearts and in the world of which we are a part.”

When we do find a meaningful path, we need to respect the integrity of teachings. Every genuine teaching — Buddhism, the Gurdjieff Work, Sufism, Esoteric Christianity, Native traditions, and others — forms an integral whole of theory and method, cosmology and stages of practice. They cannot be splintered without distortion and damage. The attitude of the spiritual eclectic often remains rooted in personal spiritual growth without considering the development of others or the impact on the teaching itself. Engagement in genuine spiritual teachings is equally for oneself, for others, and for the world itself. Indeed, the aim of one’s own enlightenment is no more important than the awakening of others and the healing of the world. Yoga teacher Michael Stone writes, “Mindfulness is… designed to reduce stress and suffering both in our own hearts and in the world of which we are a part.”

One of the great dangers in the climate of today’s spiritual search is what I would call “a little here and a little there” — the smorgasbord approach. We take this technique and idea from this teaching, and this philosophy and method from another teaching based on what we think is right for us. This often takes the guise of “seeking my own truth” and is really just a manifestation of our lower nature, what Ken Wilber calls “the ego in drag.” It can also be highly destructive to the teaching itself, giving rise to all manner of distortions and misunderstandings.

The Dalai Lama teaches that the global dissemination of spiritual teachings is very healthy, giving seekers an opportunity to experiment with different paths to find what is right for each person’s temperament and being. But, he claims, we need to find one teaching and make some level of commitment to genuine study and practice. Each teaching is whole; in a sense it is larger than we are, and it’s aims and methods cannot be taken apart without diluting its potency and capacity to assist us in a transformation of being. The spiritual search is not just about me; changing this attitude will alone make an enormous difference in the way in which we explore teachings, ideas, and our inner work.

The Dalai Lama often reminds us that the greatest impediment to our awakening is self-centeredness. When we begin to perceive the interconnectedness of life the unity of all things, we draw strength and inspiration from this larger perspective. We are not in this alone. All human beings share many of the same challenges and possibilities. Both courage and compassion derive from the epiphanal recognition of our profound kinship with each other and with all living things.

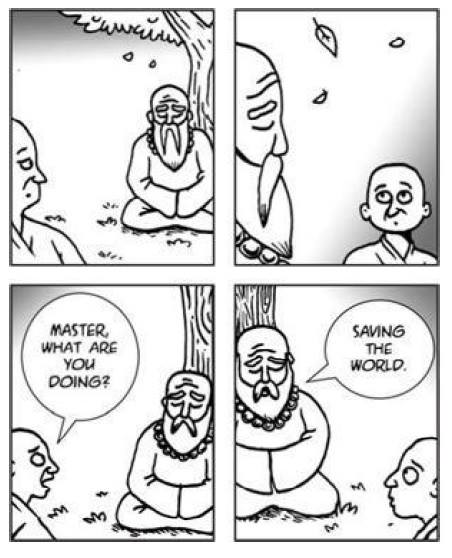

In For Common Things, young scholar Jedediah Purdy eloquently argues: “Our liberty means unprecedented power to neglect the questions that tradition addresses, and that responsibility to any commons relies upon: …Whose well-being is in my hands and in whose hands is mine?” This question redirects into our lives the light of Buddha’s teaching and the purpose of the bodhisattva’s great vow: to help all sentient beings and to assist all others on the path with skillful means. It offers a new perspective for caring, intelligent individuals that remains fully aware of human folly, but encourages us to keep on trying—bringing our wisdom to others with persistence, detachment, and the unshakable conviction that the world is worth saving and that we can transform and evolve as individuals and a race.

______________________________________________

In this post, we have tried to raise the relevant questions and lay the groundwork for a series of upcoming essays. We welcome your comments on this ongoing dialogue: dulrich@creativeguide.com