Can you name an image that has endured in your mind and served to alter and expand your consciousness? I remember many but a few stand out from my formative years.

As a high school senior in 1968, I can never forget an afternoon outing with my girlfriend to the Cleveland Museum of Art. After viewing the different galleries and collections, long dormant energies in me began to awaken. We then entered the Arts of India wing of the museum, a collection that is one of the finest in the world. I stood in front of the classic statue of Shiva Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance, Hindu god of death and rebirth, intuitively feeling the force of the symbolism and the many-layered content of the maker’s expression. I marveled that the power of the statue and its meaning could still reach me thousands of years later. I made a ritual gesture of photographing the statue, not only for the sake of memory, but also to acknowledge and honor its inherently evocative forces. The powerful impression made on me by the statue was unforgettable though I was mostly unaware of the range of its symbolic content.

What I did recognize in the statue was the intricate dance between creation and destruction within a grand sweep of life. This impression has never left me and continually reminds me that within the temporality of life lies an endless dance of endings and beginnings that can be tempered by courage, awareness, and acceptance.

The second image, also from 1968, influenced an entire generation and is widely credited as being a catalyst for the growing environmental movement. Nature photographer Galen Rowell has named Earthrise, taken by Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders, “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken.” Astronauts in space routinely offer accounts of a transcendent awe in looking back at the earth from space, an experience of a cognitive shift known as the “overview effect,” that is powerful enough to be lifechanging. Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell says, “something happens to you out there,” and describes his experience as “interconnected euphoria.” He recounts,“You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it.”

I believe that for me and many others our first view of this photograph was nothing less than astonishing to see our fragile, blue planet suspended in space devoid of national boundaries, ideologies, and the machinations of the human race. This may sound naïve from our current perspective, but it made us inalienably aware that the earth was a sentient, living being and not just the inert platform upon which we unconsciously lived our lives. I now think that some measure of the overview effect took place upon my generation merely from seeing the photograph for the first time.

Another constellation of images that emblazed themselves upon my mind and being came from watching the Vietnam war unfold in magazines and on the TV. In those days, the military did not censor or control journalism from the Vietnam war with anywhere near the same measure as today. Photographers were on the front lines and did not shirk from telling the truth about the violence, inhumanity, and abuse from both sides of the battle lines. The dispatches were horrifying in their reality and intensity. These images and video clips helped ignite the anti-war movement that became one of the largest and longest protest movements in the country rivaled only by the more or less simultaneous civil rights movement.

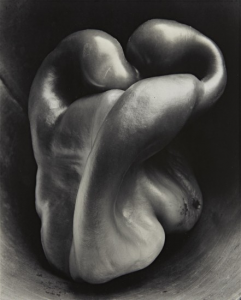

And finally, in 1970, I traveled from my hometown in Ohio to visit the galleries and museums in New York City. At Witkin Gallery, one of the first galleries entirely devoted to photography, I encountered an original print of Edward Weston’s iconic image, Pepper #30, 1930 (printed by his son, Cole). It stopped me in my tracks in a moment of great aesthetic force. I knew, or rather sensed in the moment, that the image penetrated deep within and changed me, expanded my consciousness. To see an everyday, ordinary object—a green pepper from a grocery store—rendered in a way that reflected the universal life force within all things screamed its power into my mind, heart, and senses. I purchased the print and look at it every day. Fifty years later and its original force has not diminished.

Edward Weston writes in his Daybooks: “My work has vitality because I have helped, done my part in revealing to others the living world around them, showing to them what their own unseeing eyes have missed.” And then later, he articulates, “Life rhythms felt in no matter what, become symbols of the whole.”

I learned through my experience of the Weston print something about how artists employ the very personal, what is close at hand, to suggest collective conditions and the eternal truths embedded in human consciousness, a kind of one mind tracing back to our early ancestors. If we believe this, then conscience dictates that, as contemporary artists, we must assume our role in representing the timely conditions of the current moment as traces in the dance of history, informing the present and contributing to the knowledge and wisdom of those to come.

As I write this essay, the 2020 coronavirus pandemic is devastating the global community with untold suffering and death. Yet, perhaps because of social distancing and respect for medical privacy, we do not yet have visual stories that show the effects of the disease on people and communities. We see hauntingly empty streets, people sheltering in place at home, and makeshift morgues in refrigerated trucks. But the human cost is still invisible unless you are living within a hot zone. This might help account for the personal liberty advocates who rush headlong into prematurely reopening stores, bars, salons, and restaurants. The economic cost of the virus has been devastating to employees and businesses. This too needs thorough documentation in visual form. But, of what value is a good meal or a fresh new haircut if you become unconscious on a ventilator fighting for your life? We need visual stories to know reality in our gut, not just in our mind.

Sarah Lewis, art historian and associate professor at Harvard, speaks to author Walter Isaacson in an interview about the necessity for visual stories by artists and photographers during the pandemic. She says, “the moment is fertile… People dig into themselves during crisis. They are able to understand their own capacities. If there is any eternal truth about the arts, it is that it forces this reckoning between who we are, who we think we are, and who we actually could be.”

This reckoning can function as a redemptive experience, reconciling one’s present state with one’s potentiality. After my experience with the statue of Shiva Nataraja in my youth, I researched the experience of the aesthetic encounter and tried to unravel how something created centuries ago could enter my being with such force in the present moment. I found a concept that answered some of my questions. Ananda Coomaraswamy, the great Indian scholar and curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, refers to a Pali word, Samvega, “to denote the shock or wonder that may be felt when the perception of a work of art becomes a serious experience.” “Samvega is a state of shock, agitation, fear, awe, wonder or delight induced by some physically or mentally poignant experience.” In my experience, great art can startle our senses, ignite the mind, take our breath away, causing us to gasp with surprise. It arrests our attention from the quotidian things of life and brings us fully into the timeless present. This “aesthetic force,” as Sarah Lewis calls the encounter with great art, leaves us changed, sometimes a little, sometimes a lot. Our consciousness expands and transforms from the encounter.

Most importantly, it shifts our awareness beyond the confines of the self and opens to awe, wonder, and deep respect for life’s manifestations. It can release our identification with the ego and untether our true nature from the often fierce attachment we have to aspects of our identity such as race, gender, appearance, body type, ethnicity, and our multiple roles in life. Works of art can reflect the entire spectrum of consciousness from the individualized ego to collective awareness and compassion and finally to an experiential recognition of life’s unity. This freedom from identification with self—engendered by powerful impressions—helps us realize the spirit of who we are within our mortal frames.

The true purpose of art then is to expand our consciousness, enlarge our perspective, and evolve our understanding of the world and others. And, as consciousness transforms through making and viewing art, so do our actions and interactions with life leading to greater empathy, justice, and enlightened decision-making.

I believe that one of the great awakenings that can come from the pandemic is a radical shift from me to we, engendering a greater collective awareness of the common good through a decisive denunciation of the rampant individualism that has been with the West since the Renaissance. And conversely, I can’t dismiss the hope that leaders in authoritarian countries (including some of the USA today) might be sufficiently humbled to recognize the value of human dignity and individual human lives. For this to happen, we need a large body of art and writing that tells powerful and moving visual stories about individuals and communities that go viral and grab us by the throat and won’t let go. Maybe the balance between individual rights and responsibilities leading to collective action can fundamentally shift for future generations.

The simple truth is that photography and art expand our awareness about both the world and ourselves simultaneously and lead us to the realization that the inner and outer worlds are inexorably linked, as in two sides of the same coin. Images can reveal our contradictions, both societal and individual, and place them in sharp relief. Art can inspire our search for understanding, foster our pursuit of happiness, and incite positive action. Art, literature, and music are shown to have the capacity to increase empathy and expand our awareness of other’s circumstances, realities that may be very different than our own. They ignite intercultural understanding through locating us in the place of another. Our imaginative capacities, fostered through the arts, can reflect our personal and societal aspirations, what is possible for us and for humanity, like nothing else can. They can also point the way, be harbingers of the future and show us the kind of world that is possible. Through the demands of particular mediums and the creative process, we can grow and evolve as individuals toward greater wholeness and deeper forms of interconnection. Harold Rosenberg, modernist art critic, writes:

“… The individual arts, in whatever condition they have assumed under pressure of cultural change and the actions of individual artists, have never been more indispensable to both the individual and the society than they are today. With its accumulated insights, its disciplines, its inner conflicts, painting (or poetry, or music) provide a means for the active self-development of individuals—perhaps the only means. Given the patterns in which mass behavior, including mass education, is presently organized, art is the one vocation that keeps a space open for the individual to realize himself in knowing himself. A society that lacks the presence of self-developing individuals—but in which passive people are acted upon by their environment—hardly deserves to be called a human society. It is the greatness of art that it does not permit us to forget this.”