Photographers from elsewhere (outsiders) can bring a fresh view, untainted by years or decades of involvement with the society, politics, and culture of Hawai‘i. Insiders, however, have an intimate view that is born of experience, fueled by involvement with the community, and driven by various impulses: documentation, celebration, commentary, and protest—or various forms of aesthetic and conceptual investigation.

Due to colonization and immigration, Hawai‘i has become a largely multicultural society, and, with the exception of Native Hawaiians, ethnicity and race are not primary markers of one’s identity. Ancestry, family, and birthplace are held in high regard, and there is a distinction between those that were born here and those that migrated from other places. Many, but not all, of the important documentary and fine art photographers in Hawaii of the last 50 years fall into the latter category. I apologize for any errors or significant omissions in this list.

Franco Salmoiraghi

Shuzo Uemoto

Wayne Levin

David Ulrich

Ed Greevy

Mark Hamasaki

Kapulani Landgraf

Boone Morrison

Jan Becket

Tom Haar

Renee Iijima

Sergio Goes

Alison Beste

Tracy Wright Corvo

PF Bentley

Dewitt Jones

Ricki Cooke

Peter Shaindlin

Mark Arbeit

Stan Tomita

Gaye Chan

Phil Jung

Hawaii is a small and highly diverse community facing major economic, cultural, and social challenges—all of which began with the arrival of European explorers and Protestant missionaries in the 19th century. The agricultural industries of the 19th and 20th centuries (sugar and pineapple) brought workers and their cultural/religious traditions to the islands from many places, such as Japan, China, Korea, and the Philippines. These industries dominated land use for centuries, occupying enormously large swaths of land to produce their crops. The real estate developments of the mid-twentieth century that built resorts, hotels, and condominiums destroyed many sacred sites and forever altered the living pulse of many districts. Add to this mix a vibrant host culture, fragile ecosystem, rapidly disappearing indigenous species, and a disproportionally large military presence on the islands, and what you have are grounds for much tension and conflicting agendas.

The arts and photography can give voice to the people of Hawai‘i, either by affirming what is special and unique about these islands, or by actively protesting the destruction of neighborhoods and cultural sites, as well as the insidious development and colonization of a place and its people.

For an individual photographer, the scope of these challenges can be overwhelming. And the importance of some of these issues to the people of Hawai‘i needs to transcend the creative expression of a single voice or artistic style. Several of key photographic projects in Hawai‘i have been collaborative with individual photographers and sometimes designers, historians, writers, and cultural leaders working together.

The first of these artistic initiatives was the book and exhibition, E Luku Wale E, Devastation Upon Devastation, undertaken by Piliamoo, the collective name of the two photographers, Kapulani Landgraf and Mark Hamasaki. E Luku Wale E consists of 125 black and white large format photographs, made mostly between 1989-1992 during the construction of the controversial H-3 highway project, a 16-mile highway that bisects the island from the Southwest to the Northeast and connects the military installations of Pearl Harbor with the Marine Corps Air Station at Kaneohe Bay. During the 1.3 billion dollar project, numerous heiau (temples), agricultural complexes, wetlands, and wahi pana (storied places) were destroyed forever—lost to upcoming generations. The photographs made by Hamasaki and Landgraf serve as the sole witness to the massive destruction and alteration of the landscape, a form of protest and a potent lament over the insensitive destruction of important Hawaiian cultural sites.

The highway offers a stunning view of the valleys and mountains of the Ko‘olau range and proponents of the project argued it would bring tourists and residents alike closer to the intense beauty of the land. This logic reminds me of the Sierra Club’s statement about the building of the Glen Canyon on the Colorado river in Northern Arizona, chronicled in Eliot Porter’s book, The Place No One Knew: Glen Canyon on the Colorado. The Army Corps of Engineers claimed that by building the dam tourists in their motorboats could now get closer to the canyon walls to which the Sierra Club replied, “Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get nearer to the ceiling.”

Landgraf has published several books on land and culture in Hawai‘i. She writes: ”I feel compelled to celebrate my Hawaiian culture, but also to express my feelings on the profound changes that have happened and continue to occur in Hawaii by ongoing Western intrusion and its impact on Hawaiian rights, values and history. Although much of my work laments the violations on the Hawaiian people, land and natural resources, they also offer hope with allusions to the strength and resilience of Hawaiian land and its people.” Landgraf and Kaili Chun are the only Hawai‘i artists who have exhibited in the Venice Biennial, in installations which were part of an indigenous arts initiative in 2015.

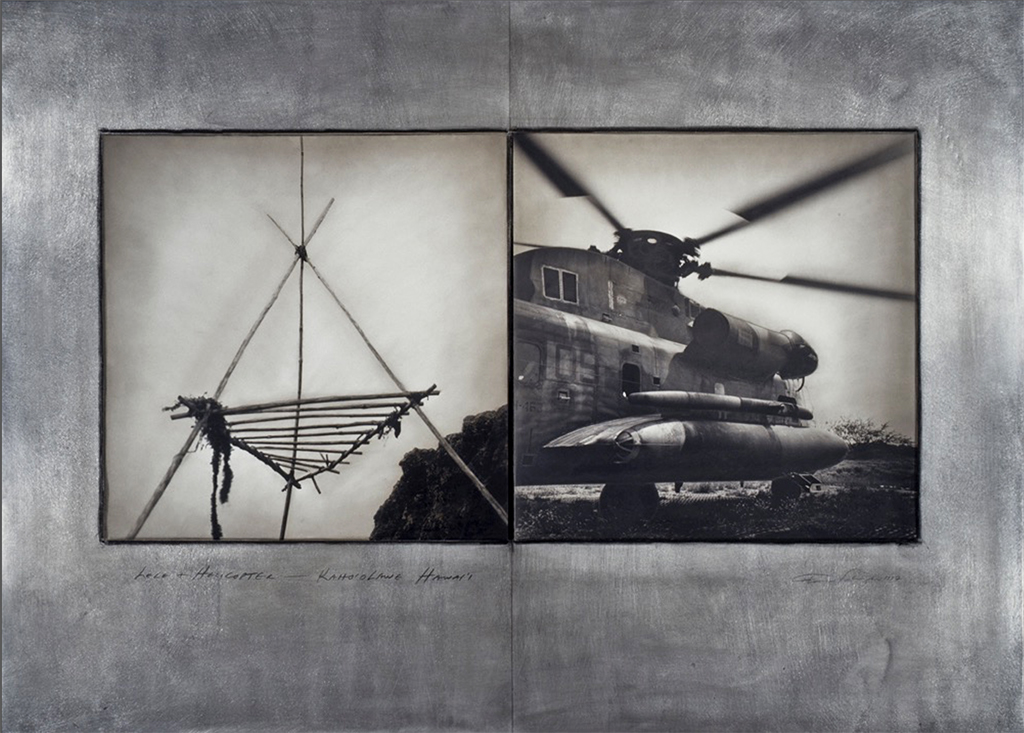

Following closely after the H3 documentation was the Kaho‘olawe project in which three photographers— Franco Salmoiraghi, Wayne Levin, and myself—and Rowland Reeve, an archeologist guide (who contributed text and additional photographs), were commissioned to photograph the island of Kaho‘olawe for the book, Kaho‘olawe: Na Leo o Kanaloa, and traveling exhibition, Kaho‘olawe: Ke Aloha Kupa‘a I Ka ‘Aina (Steadfast Love of the Land). We had collaborated and exhibited together before the project and our work was reasonably well known within the state.

Kaho‘olawe is the smallest of the eight principal Hawaiian islands and lies in the leeward shadow of Maui’s Haleakala volcano. Kaho‘olawe is sacred to the Hawaiian people, containing over 3000 inventoried archaeological sites, and was used by the US military from 1941 to 1991 as an ordnance training range. Thousands, if not millions, of shells and other explosives, weighing up to 500 pounds each, were detonated on the island and in the surrounding waters.

With the exception of some of Franco Salmoiraghi’s documentation of the early illegal access to the island by Hawaiian activists, most of our photographs were made between 1993-94 from over a dozen trips to the island during a narrow window of time—after the bombing ceased in 1990 and before the ordnance cleanup began in the mid-nineties.

We were asked only to experience the island, spend time within its shores, explore its different sides, participate in the activities of both the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana and the US military explosive ordnance teams, and to generate visual images in accord with our own observations. We were given a rare opportunity — and a great responsibility. The project highlighted the cultural importance of the island as well as the destruction wrought by 50 years of occupation by the military. The exhibition traveled throughout the state and closed at the Smithsonian in Washington in 2002. Between the state-wide venues and the Smithsonian, the exhibition was viewed by over 350,000 people, a tribute to the social and symbolic significance of the island.

Those who have the privilege of spending much time on Kaho‘olawe tend to be deeply affected by the experience. What it is that we find so moving is hard to express. Perhaps it is the island’s physical beauty, its mingled sense of tragedy and hope, or the powerful lingering presence of ‘ka po‘e kahiko’, the people of old.

—Rowland Reeve, Introduction to Kaho‘olawe: Na Leo o Kanaloa

Franco Salmoiraghi and Wayne Levin have made a lasting mark on the arts and culture of Hawai‘i through their images. And I have been very active in the community as a photographer, writer, and teacher. Salmoiraghi, one of Hawaii’s most important and versatile artists, has been making images here for nearly 50 years as an editorial and fine art photographer. He has graced the covers of numerous magazines, told countless stories, and been a contributor to numerous exhibitions in galleries and museums, here and elsewhere. Several of his core projects include the demise of the sugar industry, images of plants and flowers, portraits of many cultural leaders, and observations of the power of the land and culture in Hawaii.

Wayne Levin, author of eight books of photographs, is known primarily for his exquisite black and white underwater work—the forerunner of many of today’s surf photographers. The only photographer from Hawai‘i to be part of the Museum of Modern Art permanent collection, Wayne has made powerful and luminous images of the creatures and objects of the undersea world since the early 80’s, including body surfers, swimmers, large mammals, predators, schools of fish and WW II shipwrecks.

Many photographers in Hawai‘i combine some form of professional work to make a living with a fine art sensibility. Sergio Goes was an editorial and fine art photographer who worked for many of the major magazines, helped galvanize the Chinatown cultural district, taught through Pacific New Media, and exhibited his work in The Contemporary Museum Biennial of Hawai‘i Artists as well as in a posthumous exhibition at Pegge Hopper Gallery titled Sergio Goes: The Seer and the Spectacle. Sergio died in a free diving accident in 2008 but not before leaving behind an experimental and daring body of work from sport aircraft, cross-country travels, and from the silent world of free diving.

Chief photographer for the Honolulu Museum of Art Shuzo Uemoto has a long history of photography in Hawai‘i, most notably with the publication of a book in 1984 consisting of portraits of hula dancers and kumu hula (hula teachers). Uemoto continues to teach photography and make fine art images and his work can be seen in various exhibitions around town.

Photographers who choose not to do commercial work for a living often teach in secondary or post-secondary institutions. Conceptual and installation artist Gaye Chan is the Chair of the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Hawai‘i Manoa. With a long history as a photographer, Chan’s work dissolves boundaries between mediums and often employs alternative presentation methods beyond the museum/gallery context, such as the web, Instagram, and grassroots public projects. As Chair of the Art Department and an active exhibiting artist, Chan has been influential to a new generation of photographers and artists. Her Eating in Public project was recently exhibited at St. John the Divine Cathedral in New York.

Most of the photographers featured in this post have been active for decades and have helped establish photography in Hawai‘i as a timely and relevant voice. They/we have shaped the medium’s influence in our island communities. However, many of us are nearing or past retirement age and we need to look towards the future. Who will heed the call to document, interpret, and comment on life through the lens? And how?

Two younger photographers—and teachers—have recently produced substantial bodies of work in Hawaii with a critical approach and represent dynamic and hopeful new directions. Phil Jung is a visiting professor in the UH Art Department and also teaches at Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. His documentary work was recently featured in an exhibition at the UH Manoa Art Gallery and focuses on local culture with a critical yet compassionate gaze.

“Jung captures many moments that a local viewer could easily find herself or himself in. Shots of families at the beach and people going about their everyday life will also be familiar, but it is Jung’s ability to remind us of the power plants, scrap yards, strangled urban streams and minimalist beach amenities that are always in the periphery that jolts the viewer’s consciousness.”

— David A.M. Goldberg, Honolulu Star-Advertiser

Alison Beste recently received her MFA from Lesley University College of Art and Design (formerly The Art Institute of Boston). A secondary school teacher and instructor at Pacific New Media, Beste comments on the human-altered landscape in a way that implies a significant challenge and threat to future generations. In her Light Pollution series, she creates images of ocean and atmosphere with a sublime beauty, until the viewer realizes the immense paradox: that the luminous color and splendor arise from air and light pollution. In a poignant glance at the sources of energy that fuel modern life, she shows imaginary “sunsets” whose actual subject is the light reflecting off oil tankers coming and going from the Honolulu port.

In an age where lurid spectacle and overblown images in which photographers strive for effect becomes the norm not the exception, all of the above-listed photographers avoid the easy and expected exoticism of Hawai‘i and its people. They try to represent Hawai‘i with honesty and truthfulness—offering the integrity of an informed point of view. Images are about something: a concept, a moment, or a standpoint that moves us, teaches us, or enhances the livingness or presence of the subject.

The myth of paradise in highly pictorial images is an easy cliché, and ultimately damaging to the necessary process of helping oneself and others learn to perceive, in James Agee’s legendary words, the cruel radiance of what is. When I was a teenage photographer, I made a series of bucolic, Ohio landscapes that were, in the pejorative sense of the word, spectacular to my eyes and undeveloped sensibilities. I went to a theatrical lighting store and bought strongly colored, acetate lighting gels that I would then ceremoniously place over my lens resulting in drama-ridden, color-infused photographs. I tired of this very quickly as I understood that the world itself commanded respect and was worthy of my interest and attention for no other reason than its very presence. We often start with spectacle and evolve towards presence.

Presence humanizes; spectacle debases.

_____________________________

Next post in the series: A New Generation of Photographers in Hawai‘i: The Aesthetics of Influence