The website of the State of Hawai‘i Film office makes the promotional statement: “Hawai‘i is an amazing place to film for so many reasons: Unparalleled beauty, a talented and hardworking labor pool, diverse locations that range from remote rainforests to urban landscapes, and a unique host culture that sets Hawai‘i apart from the rest of the world.”

I have been photographing in the islands for three decades and teaching photography in Hawai‘i for twenty-five years both in a university setting and in community programs. Since 1995, I’ve been developing programs and teaching for Pacific New Media, University of Hawaii Manoa. We have recently been named by Honolulu magazine as the “Best Photography Classes” in Honolulu for 2016. It is an honor and privilege to receive this award.

What do I find photogenic and stimulating about Hawai‘i? I experience an intensity in the atmosphere, a sense of the living land as being instilled with significance. The influence on the land by diverse people imbues it with presence and tragedy, mixed into a powerful amalgamation of forces. Hawai‘i is like nowhere else on earth.

I often realize with startling force that I am here on a tiny speck of land in the midst of a great ocean, thousands of miles from anywhere. A mere 7 million acres of land comprise the principal Hawaiian islands. Further, the topography of the volcanic archipelago, with steep mountains extending to the sea, means the inhabitable land is limited to small tracts of earth between the ocean and the foothills and within the verdant valleys between the peaks. The land has power and force. Its great value stems partly from the sheer newness of its volcanic genesis, partly from the influence of the ancients who infused the land with deep respect and symbolic meaning, and partly from its scarcity.

The landscape of Hawai’i generously reveals the evidence of the forces which shaped, and continue to shape, its existence. The action of volcano, wind, water and the presence of man — both ancient and modern — have left their distinct marks, resulting in a land of great mystery, beauty and awesome power.

The central conflict of land use in Hawai‘i revolves around the fact that Western interests view the land as a commodity—something to be bought or sold and exploited for economic gain. In Hawaiian thought and sensitivity, the land is seen as a living being that cannot be possessed, the vehicle through which unseen forces pass, a link to the earthly presence of the gods.

In the post-colonial society that now governs every aspect of life in Hawai‘i, we face overdevelopment, depletion of natural resources and rapid extinction of unique species of plants and animals, and an erosion of economic security for many island residents. Land tenure issues create great tensions between missionary-descendant land owners and both immigrants and Native Hawaiians. There is much for the camera to witness and record.

Thus, many photographers from elsewhere have come here to create bodies of work. From the great modernist photographers such as Ansel Adams, Minor White, and Brett Weston to contemporary photographers such as Linda Connor, Richard Misrach, and Debra Bloomfield, Hawai‘i has an illustrious history of providing the subject matter for many diverse and important bodies of work. A partial list of photographers who have created bodies of work entirely or partly in Hawai‘i include, in loose chronological order of the time of their visits. I have excluded photographers who live full or part time in Hawai‘i.

Ansel Adams

Minor White

Aaron Siskind

Brett Weston

Walter Chappel

Jerry Uelsmann

Annie Liebowitz

Linda Connor

Stephan Brigidi

Stu Levy

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Spencer Tunick

Richard Misrach

Debra Bloomfield

Elaine Mayes

Len Jenshel

Diane Cook

Geoffrey Fricker

Daido Muriyama

Thomas Struth

Doug Beasley

Richard Renaldi

The torrent of photographers visiting Hawai‘i began in 1948 when Ansel Adams arrived to take photographs for a series on National Parks, funded by the Department of Interior and later by the Guggenheim Foundation. In the 1950’s, he returned to work on a Centennial book, The Islands of Hawaii, for Bishop National Bank (currently First Hawaiian Bank) and produced a comprehensive examination of the land and people in the pre-Statehood era. His photographs reflect a post-war idealism and do not address the complexity and repression of colonialism. His stance was clearly pro-Statehood and scholar Jonathan Spaulding described his work as having a “tone of triumphant nationalism.” In the 1990’s, Elaine Mayes, a Professor Emerita at NYU and a 1991 Guggenheim Fellow, completed an insightful, sweeping photographic project resulting in Ki‘i No Hawai‘i, a limited edition book about land, culture, and change in Hawai‘i. The natural and social fabric of the islands have undergone many changes since these projects, and the conflicts over land is a key factor in both the struggle for indigenous rights and in efforts toward a sustainable and intelligent use of land and resources.

In the past twenty-five years, three Bay Area photographers have frequented the islands, creating substantial bodies of work. Linda Connor investigates sacred sites around the globe, including Hawai‘i with an 8X10 view camera, film, and Printing-Out paper, an emulsion exposed directly by sunlight, resulting in warm, mysterious tonal renditions. Richard Misrach created his celebrated On the Beach project from the Kaimana Beach hotel on Sans Souci beach in Honolulu exploring the often uneasy relationship between people and the edge of the powerful, unpredictable ocean. And Debra Bloomfield created her book, Still: Oceanscapes, from the same beach in Honolulu where Robert Louis Stevenson, the writer, used to sit under the shade of an over a century old Hau tree.

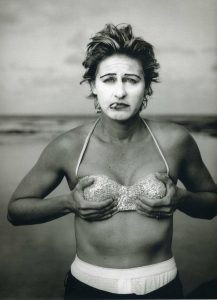

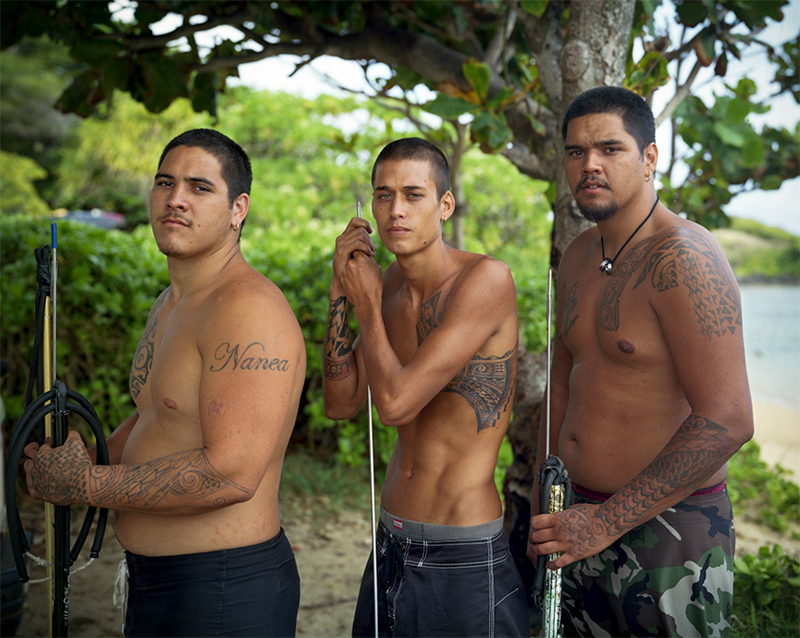

Len Jenshel and Diane Cook, an accomplished husband and wife team, included many potent images from Hawai‘i in their book, Hot Spots: America’s Volcanic Landscape. While most of the other photographers listed here have focused on the beauty and mystery of the land, Annie Liebowitz has published beachside portraits of Mick Jagger and Ellen DeGeneres, and Richard Renaldi, a former student of Elaine Mayes and a 2015 Guggenheim Fellowship recipient, explores body language and a physical vocabulary through portraiture in his project on the islands.

As a landscape photographer myself—indeed the power of the land is what partly drew me to Hawai‘i thirty years ago—I have several deep concerns. The myth of paradise is a paradox. Do a Google internet search for photography in Hawai‘i and what will you find? Sunsets, weddings, palm trees, and generally superficial, oversaturated landscapes. We idealize paradise and ignore its deeper meaning. Where is the bracing, hard-edged incisive documentary work that uncovers environmental challenges, social injustice, prevalent poverty, and the lives and plights of real people?

I feel strongly that all of us, insiders or outsiders, who consider ourselves artists need to go deeper, farther into the beautiful, mysterious, haunting, and complexly conflicted soul of Hawai‘i in the modern era. I am perpetually waiting for more photographers to come along that will document, through a penetrating lens, the beauty and tragedy of what is real in these islands. I resonate with Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s poem, I Am Waiting, from his classic book of poetry, Coney Island of the Mind. Just substitute the word America with Hawai‘i.

“I am waiting for someone

To really discover America

And wail …And I am perpetually awaiting

A rebirth of wonder.”