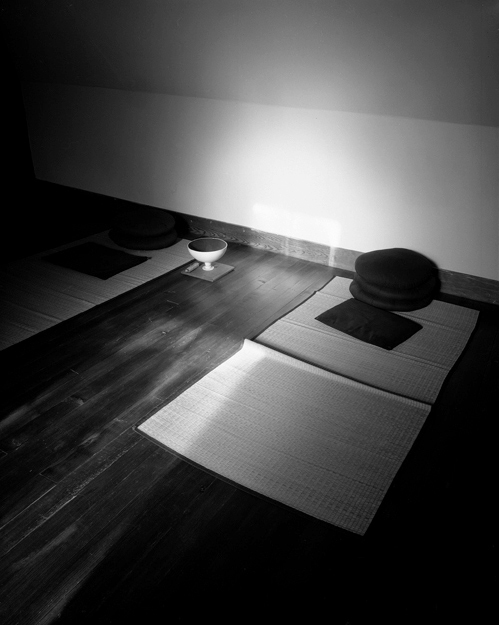

One of the many paradoxes found in Zen is the complex relationship between single-pointed concentration and an expanded, unconstricted awareness. These may seem like diametrically opposed experiences when, in fact, they are viewed as two sides of the same coin in Zen—comingling with each other in a single spectrum of consciousness. The inward look and concentration on one’s breath in Zen sitting often open outward to a deeper connection with life and a sharpened attention with a camera.

The fluid awareness at the heart of Zen practice unleashes our true human potential. Human beings are gifted with sight, both literally and figuratively. What we see, we are. The action of becoming quiet and releasing tension unleashes vision and can bring you more in touch with your internal wisdom and the world itself. Our usual tensions, preoccupations, and habitual attitudes block clear seeing and the potential for a creative response. The mind is rarely a clear, reflecting organ. Krishnamurti reminds us of the simple effort needed to learn and to truly perceive: “Now, is there . . . space in your mind? Or is it so crowded that there is no space at all? If your mind has space, then in that space there is silence—and from that silence everything else comes, for then you can listen, you can pay attention without resistance. That is why it is very important to have space in the mind. If the mind is not overcrowded, not ceaselessly occupied, then it can listen to that dog barking, to the sound of the train crossing a distant bridge, and also be fully aware of what is being said by a person talking here. Then the mind is a living thing, it is not dead.”

He later states unequivocally: “The quiet of the mind is intelligence.”

A clear paradox becomes evident. Art school teaches that the eye of the beholder is biased. Zen practitioners aspire to radiant, clear perception into the nature of things—to see the suchness of things; to see what is. Zen masters teach that the mind can be a blank slate, reflecting all that falls on it. Which is true—the sheer subjectivity of perception or the potential for impartial, even objective observation? For photographers, both poles of perception have great value. How you approach this dialectical view of perception often forms the very content of your work. Like many things, your approach depends on your attitudes and your maturity. The way one perceives is a reflection of the inner evolution of the perceiver. The challenge that a photographer forever confronts is found in the dynamic interplay between seeing things for what they are compared to seeing things based on how you are. The biases, predilections, and points of view of the photographer are what makes an image interesting and invests it with meaning. On the other hand, the world exists apart from who you are. The world and others deserve respect, care, and attention for their own sake. Great photographs have been made on the subject of one’s identity arising from autobiographical inquiry. And an equal number of powerful photographs have been made through direct perception of life itself.

This forms the great lesson of photography. We can see how we see. We can witness our thoughts and reactions to the thing in front of us, and see something of its true nature and ourselves simultaneously. Our pictures are about our relatedness to what we see. We can be liberated, even if only for moments, from the tyranny of conditioned thought and preconceptions, and see things in their radiant glory. And we can begin to discover the shape of our own nature. Photography teaches and demands both: a deepening self-awareness and an evolving relationship to the world itself. This dual awareness is a key element of photography’s potency as an expressive medium.

Excerpted from Lesson Two: Awareness, from Zen Camera: Creative Awakening with a Daily Practice in Photography, published by Watson-Guptill/Ten Speed Press. Release date, February 13 and now available for pre-order from Amazon (30% pre-publication discount), Barnes and Noble (30% discount), and Indie Bound.