The Power of Direct Perception

My predilection is to see, because only by seeing can a man of knowledge know.

—Don Juan as reported by Carlos Castaneda

First I must look, then I must learn.

—Theodore Roethke

We have become a nation of specialists. This is a good thing since it allows all individuals to find an area of focused interest that corresponds closely to their talents and predilections. My specific area of interest and knowledge in life is in learning to see. I equate seeing with questioning in the form of ongoing learning and knowing. It is not a very popular pastime. Most people prefer movies or television or the internet, or some form of mediated visual impressions. I often feel out of place, a bit of an anachronism. When I writeabout learning to see, most people stand back and state, with a certain incredulous expression, “well . . . I already know how to see.” It is no longer an inquiry or a question. Most people take vision for granted and do not realize the depth of knowing that it can engender and contain.

In the face of ever-increasing forms of stimulation, can we renew our capacity (and interest) in simply observing the world around us? We hold the potential for direct observation in the present moment, in the very midst of our lives.

Cultivating our gift of observation has many benefits. On an obvious level, we can recognize ill-intent and conditions of danger. We can be attuned to our surroundings and learn to respond accordingly, making the necessary adjustments to ensure the well being of ourselves and those within our care. Our lives can be smoother, safer, and more comfortable. We can navigate our professional lives and our interpersonal contacts with greater grace, ease and elegance. And we can learn to assist others more effectively, reading the subtle image of their motivations, actions, and character.

We can we more awake to and aware of the myriad manifestations of the world around us. Life can pass through us, deeply informing our nature and nourishing our very being. We can even say that careful observation—of our surroundings, of others, of ourselves—is a form of food that our psyches cannot do without. We can become a greater part of life, of this moment and all that it contains. Impressions will enter us with greater force and we can see and appreciate the energies behind surface manifestations. We will be immeasurably enriched and we can become more responsible as citizens—and as parents, teachers, lovers, or friends.

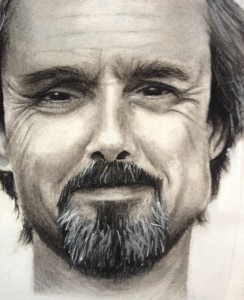

In learning to see, an art medium helps. I take photographs to expand my awareness and vision, while Laura has renewed her interest and talent in drawing. Her recent insights and observations on the connection between art and perception are noted in italics.

It’s all in the Details: The Power of the Nuance

Every detail bespeaks the whole. Every nuance is the key to perceiving someone’s character or state of being in the moment. Pay attention to subtle details, not only with your mind, but with your body and feelings as well. In his marvelous and insightful chapter on Observation in the book, Acting: the First Six Lessons, author Richard Boleslavsky claims that “The gift of observation must be cultivated in every part of your body, not only in your sight, and memory.” The change of rhythm or intonation in another’s voice, the lightning-fast shift in facial expressions, and the subtlety of minute gestures cannot be hidden from careful observation, and can reveal much important information. Listen and look with your body and your feelings to discover these changes of nuance and what they may mean.

There has been an expansion of vision (literally)—I have a broader range of sight. I look more expansively. I see more things. The sky, the trees, the birds. I see them first as single entities, and then I see them as part of greater whole, because this is the creative process — moving inward and outward — seeing things in parts and then seeing all things entirely.

Staying Open

The greatest difficulty most people have with this form of observation lies within our inherent subjectivity and the need to form conclusions based on associations and past experiences. We need to stay open to observing the moment and all that it contains. The aim here is to accept our responses, observe them merely as part of the overall landscape, and not to identify with them immediately. We do not allow these inner attitudes to prevent an ongoing—moment to moment—recording of impressions. Can we allow the scene to unfold within our field of observation in spite of our judgment and remain open to what we see?

The exercise that helps here is a simple one. Try to be quiet; view the mind as a still, reflecting pool observing everything, favoring nothing. Krishnamurti uses the phrase, “choiceless awareness,” which is like the sun, illuminating all things equally under its glance. I have found that it helps to strive to observe without words, without verbal concepts interfering with our observations. Try, for a few minutes—to see without words; you will find it nearly impossible. But, in the effort itself, something may come alive. Become a witness. Allow both the impressions of the outer world and inner world to register themselves on the sensitive field of your body, mind, and feelings. This form of observation then becomes a kind of food, a form of psychic nourishment. The pupil who is taught by the elder statesman of the theater in Boleslavsky’s book reports that exercising this form of silent observation has made her life “rich and wonderful.” She claims: “… In three months’ time I became as rich in experiences as Croesus is in gold. … Everything registers … somewhere in my brain… I’m ten times as alert as I was.”

There has been a reduced tendency to make judgments about people and things. Art, and more specifically drawing, requires that the artist let go of concepts, like eyes, face, and hair. The artist must see tones, colors, line, shape and space. Concepts and ideas result in work that looks cartoonish and like a collection of caricatures.

Instinct and Intuition

In this form of silent awareness, one attribute of seeing may emerge that gives depth to one’s observations. It could be called a state of “no-mind,” where one sees and knows from a different place than the ordinary mind. We may begin to sense and feel certain characteristics about the subject or understand something of its inherent nature through the language of instinct, feeling, or intuition. One of the distinguishing features of the emergence of these more subtle ways of knowing is that we are more anchored in the present moment, aware of our own inner world of sensation and feeling while we are observing the subject. And we often find things that we were not looking for. In a certain sense, we allow the subject to act on us, registering the energy of its impressions within our own energy field.

By staying within, we may find that while observing an outer scene, something emerges: a still, small voice, a subtle feeling, a “blink” of insight that rings true, that offers a substantial way of knowing that simply appears on the horizon of the mind.

Active Empathy

With objects, works of art, or even with people, we can employ a form of looking that is highly penetrative and potent; it is known as active empathy. And it provides much information about the subject, well beyond the mere observations of the mind. In this form of looking, we literally strive to place our attention within the object of our glance, and experience its postures, gestures, tones within the field of our own bodies and feelings. You are literally internalizing the energy of another person, or scene, allowing it to penetrate more deeply within you.

Think of yourself as a tuning fork; all impressions of the outer world resonate within you. Everything that exists in the outer world also exists within us. If we allow life to penetrate our boundaries, a similar energy within us can be evoked. We can know the nature of what is in front of us in reliable ways, using the internal sensations of our own body as a sounding board.

There has been an increased awareness of others and self. My preferred art form, portraiture, is one where the artist in many ways become intimately connected with the subject. The artist enters into the subjects emotional state in order to understand what the eyes look like when one is happy, in love, or sorrowful. Empathizing with the subject often result in the artist also experiencing the same feeling.

When compassion is engendered and walls dissolve, the likelihood of spiritual absorption and connection seems like a reasonable outcome.

Afterimage and Recall

In college art classes, we occasionally employ a marvelous children’s game—to train the capacity for observation, to expand one’s experience, and deepen the interpretation of works of art. The rules are simple. You first look at a photograph, a painting, or an outer scene for a predetermined period of time, say two or three minutes. Then you turn your attention away from the object, and you recall—everything that you can. You revisualize the scene. And you will be surprised just how much you remember. The mind has depth and dimension. It sees and registers many details that may not be within our field of conscious awareness. You will perhaps be surprised which details emerge in your mind’s eye as those which occupy a place of importance or prominence. And these important details may not be those to which the conscious mind has assigned much meaning.

The creative process works in its own time, has its own integrity. It does not always follow a linear progression. Once you have internalized an impression of an outer scene, moments of recall may take place spontaneously when you least expect it. The material that has been registered by the unconscious will spring to the surface, when it is ready, like a rose in bloom and offer moments of understanding. The mind digests its impressions in its own time, in its own mysterious fashion. Welcome these moments. Let it be, and draw what material you can from these unexpected gifts.

What Does it All Mean?

How do we draw conclusions, render a judgment fairly, make intelligible sense out of the moment of observation? The danger here is obvious, and relates to snap judgments or knee-jerk reactions that arise before all the facts are in evidence. Genuine evaluation extends well beyond our likes and dislikes, beyond our predisposed assumptions and attitudes, and beyond the activity of the rational mind. It is found in our capacity for contemplation, turning something over and over in the mind, until a creative moment of understanding occurs, and we graciously recognize that here is the insight we are seeking, here is a state of integrated knowing that is the result of our previous work.

We need to contemplate, to allow the impressions we have received during direct observation and the recall stage to act upon us and distill themselves within us. Contemplation is an activity of gestation, an active process where we attend with the mind, and turn something over and over again, allowing it to follow its own meandering stream. I have often taken questions and placed them within the contemplative factory of my mind—and days, weeks, or even months later, insights arise unexpectedly and bring both surprise and delight. The mind relaxes, and in that relaxation, a different form of thinking may occur, one with greater depth and dimension that brings new understandings in its wake.

The world contains a breathtaking amount of knowledge: in science, mathematics, the arts, the humanities. And it contains a growing body of knowledge about human evolution, both individually and as a society. And most of this knowledge was derived from careful observation, from the contributions of many people that took place over generations, over thousands of years. Present generations build upon the discoveries of their antecedents, and add to this evolving sum of knowledge that lends meaning to our worlds and to our lives.

Now it is our turn to observe and add to this growing sum of human knowledge.

The future is in our hands.

Do we have the courage to see what is?

“In a world where education is predominantly verbal, highly educated people find it all but impossible to pay serious attention to anything but words and notions. … The non-verbal humanities, the arts of being directly aware of the given facts of our existence, are almost completely ignored.… Systemic reasoning is something we could not, as a species or as individuals, possibly do without. But neither, if we are to remain sane, can we possibly do without direct perception … of the inner and outer worlds into which we have been born.”

—Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception

2 Comments

Comments are closed.