Who am I? Who are we? As a teenager, these questions ignited my mind as I sought to give shape to my longing for answers. I turned to reading autobiographies, most of which left me cold and uninterested in the mere details of someone’s life, even the famous and accomplished. What gives resonant meaning to art and writing? The question leads to a paradox. The greatest art, the most memorable writing, is infused with deeply felt personal experience or highly unique observations. Yet it points beyond the self to the human condition. When teaching a class, Maya Angelou would write on the blackboard for students of differing races, ages, backgrounds to deeply consider: “I am a human being. Nothing human is alien to me.”

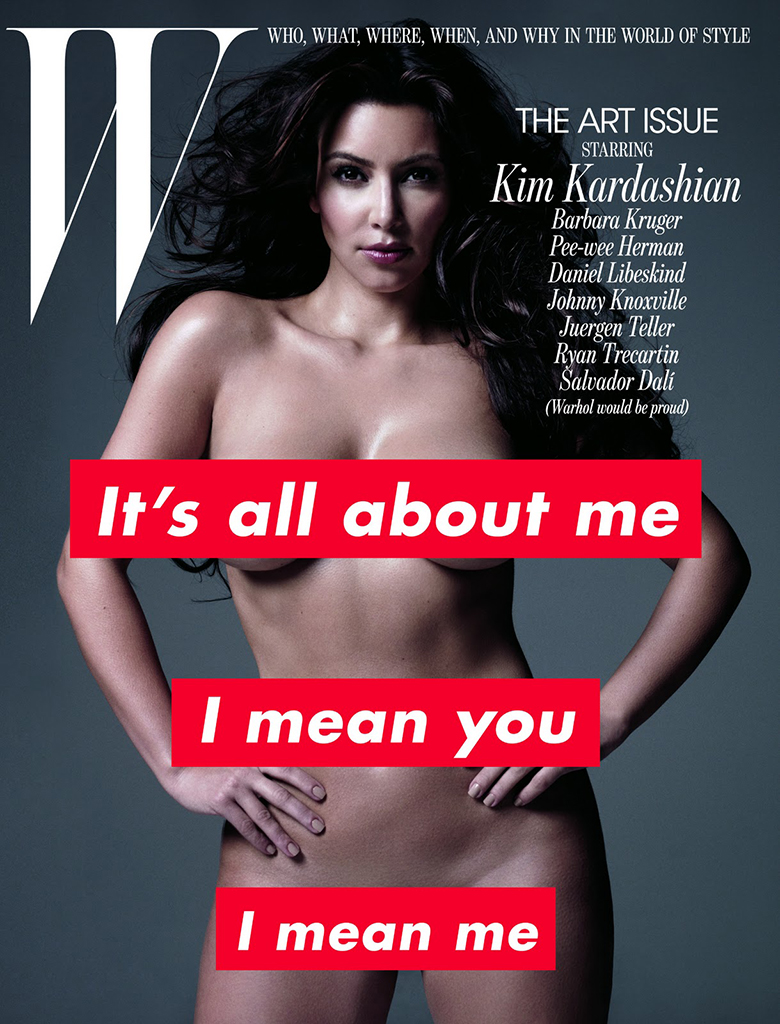

Here, however, I must question the trend that has spawned a spate of published memoirs and a host of idiosyncratic, personal styles of art. Partially due to the ease of digital creation tools, we can now find a bewildering profusion of memoirs (searching the topic on Amazon now yields 325,000 books) and a mind-numbing plethora of photographs that grace the web and social media. In this confessional culture of books and images, part of me feels: who cares? You had a difficult childhood. Write a memoir. You traveled to interesting places. Write a memoir. You need therapy. Write a memoir. You have some defining characteristic or experience. Write a memoir. Or, you see something personally memorable. Take an Instagram. And instantly make it look like a nostalgic memory from a time you never actually knew. Have good meal. Pull out your ever-present cell phone camera. It’s just too much about self.

Neil Genzilnger writes in The Problem with Memoirs in the NY Times: “A moment of silence, please, for the lost art of shutting up.

There was a time when you had to earn the right to draft a memoir, by accomplishing something noteworthy or having an extremely unusual experience or being such a brilliant writer that you could turn relatively ordinary occurrences into a snapshot of a broader historical moment. Anyone who didn’t fit one of those categories was obliged to keep quiet. Unremarkable lives went unremarked upon, the way God intended.”

One exercise taught to me by my photography teachers and reinforced within my own classroom experiences with students is to refrain from using the word “I” for a short period of time. How long can you sustain this effort? Generally, not long. The value of it, however, lies in seeing just how often and how automatically we relate everything back to ourselves. By contrast, photography and much good writing excels in detailed observations of the outer world and people. To be sure, we use our self as an instrument of discovery—our senses, feelings, minds—but not as the center around which all things revolve. At least hopefully not. There is no Zen riddle here. The world exists outside of ourselves. A big, beautiful, tragic, sad radiant world.

To argue the other side, we also exist. Our inner worlds, including our potential and our actual range of experiences, are at least as wide and deep as the outer world. We are microcosms of the macrocosm. This too demands exploration and expression. The unexamined life goes nowhere. In memoir writing, as in art, it is a question of inclusion and balance, leaving nothing out, neither inner nor outer, but integrating the two. It’s not about me, in writing or photography; it’s about what I have discovered and learned and gained understanding of through the blood of my efforts. Good writing and great art integrate both mirrors and windows.

Recently, I realized with startling force that one of my all-time favorite books is in this particular style of writing that I often find questionable. Walden is a memoir! Thoreau’s recount of his time at Walden Pond is both deeply personal, truly amazing in its observational detail, and highly social in the manner that it helped shape the American consciousness: our deep and abiding love for wild places, our self-reliance, and our meditations on the social order.

Walden is brilliant in its evocation of subtle, natural detail, its reflection of Thoreau’s inward journey of awakening, and its view of natural life as a symbolic force. Robert Adams writes on photography, and could just as easily be said of writing: “Landscape pictures can offer us, I think, three verities — geography, autobiography, and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together… the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep intact — an affection for life.” Geography, autobiography, and metaphor; the sensitive blend of these three factors gives images and words weight and meaning, power and social substance.

At this particular stage in my life and work, I am considering writing a memoir and have made tentative forays into personal essay writing. I think I may have something to offer, but do not want to contribute to the “bonfire of vanities” that plague highly personal contemporary expression. I have struggled for thirty years to understand a singular, life-altering experience. Can I now finally speak about what I have come to understand about seeing from losing my right dominant eye in an impact injury in 1983? I’m just not sure thirty years is enough. One truism I have come to respect—you cannot write about something until well after the event. Memoir-writing experts tell you not to write about an experience for twelve years. Another says twenty years. I’m not sure if I yet have the wisdom—or the ego—to use my own distinctly personal experience to help others find greater luminosity and clarity through sight. In my book, The Widening Stream: the Seven Stages of Creativity, one chapter titled “A Personal Account” details my experience with partial blindness and what I have learned thus far. People that read it say they are very moved. The chapter was recently excerpted by Parabola magazine with the title, Awakening Sight.

While I fully acknowledge the value of the memoir exercise for personal therapy, or oral histories or family remembrances, it is a question, for me, of scale and reach. This form of highly personal recollection is vital to communities and families and individual lives. Many suitable platforms for autobiographical expression can be found: blogs, social media, family archives, personal journals and diaries, Blurb books, and more. Like water, everything must find its own level. Not everything is destined for Random House or the Museum of Modern Art. Nor should it be. For a memoir or highly personal body of work to leave our intimate circle, or our close community, I feel that we must apply a litmus test, a measured standard.

In Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, William Zinsser writes: “A good memoir requires two elements—one of art, the other of craft.” Does it sing? Does it have what Zinsser calls, “integrity of intention?” Can it elegantly reach others with a compelling story relevant to the reader’s life? We respect triumph and human fortitude and resiliency of spirit. We want to learn things through the experiences of others. Your voice becomes primary in what it teaches, shows, or demonstrates.

And is it written well—crafted to high standards, with your own voice and your own unique style? Interesting experiences do not always magically find their own shape on the page. We need to assist the process. Thoreau wrote seven drafts of Walden over eight years. In doing so, Zinsser remarks, “He wrote one of our sacred texts.”

How can we convey timely and individual experience in a universal manner that touches both a unique personal fabric and the depth of the human condition?

Among the great lessons of art is the cultivation of empathy and compassion. “Unitas Multiplex”, universal pluralism, the many contained within the One, could be the right manifesto for the arts and culture of our age—cultivating openness, universal understanding and broad tolerance—a recognition of our profound similarities while acknowledging our real differences. Paul Theroux writes of this: “There is a paradox… the deeper I have gone into my own memory, the more I realized how much in common I have with other people. The greater the access I have had to my memory, to my mind and experience …the more I have felt myself to be a part of the world.” He goes on to speculate on the political dimension of the creative process, seeking the ground of our common human heritage and trying to identify the size of the plot where are we genuinely, unambiguously different. He echoes the feeling of many that the recognition of both our shared conditions and our individual variations, are equally necessary to contribute to the dialogue of our times.